Two weeks ago I´ve had an appointment in the Cranchi shipyard, a family owned Italian high grade power boat manufacturer, around since 1870. They are producing absolutely high class yachts from 26 to 78 feet at the beautiful North Italian Lago di Como. “Industry 4.0” is not just a marketing term for them, but reality. I highly recommend my article “What if?” about Cranchi, in which you can see their amazing manufacturing quality – and watching me fantasizing having Cranchi making sailing yachts as well, which would be unseen …

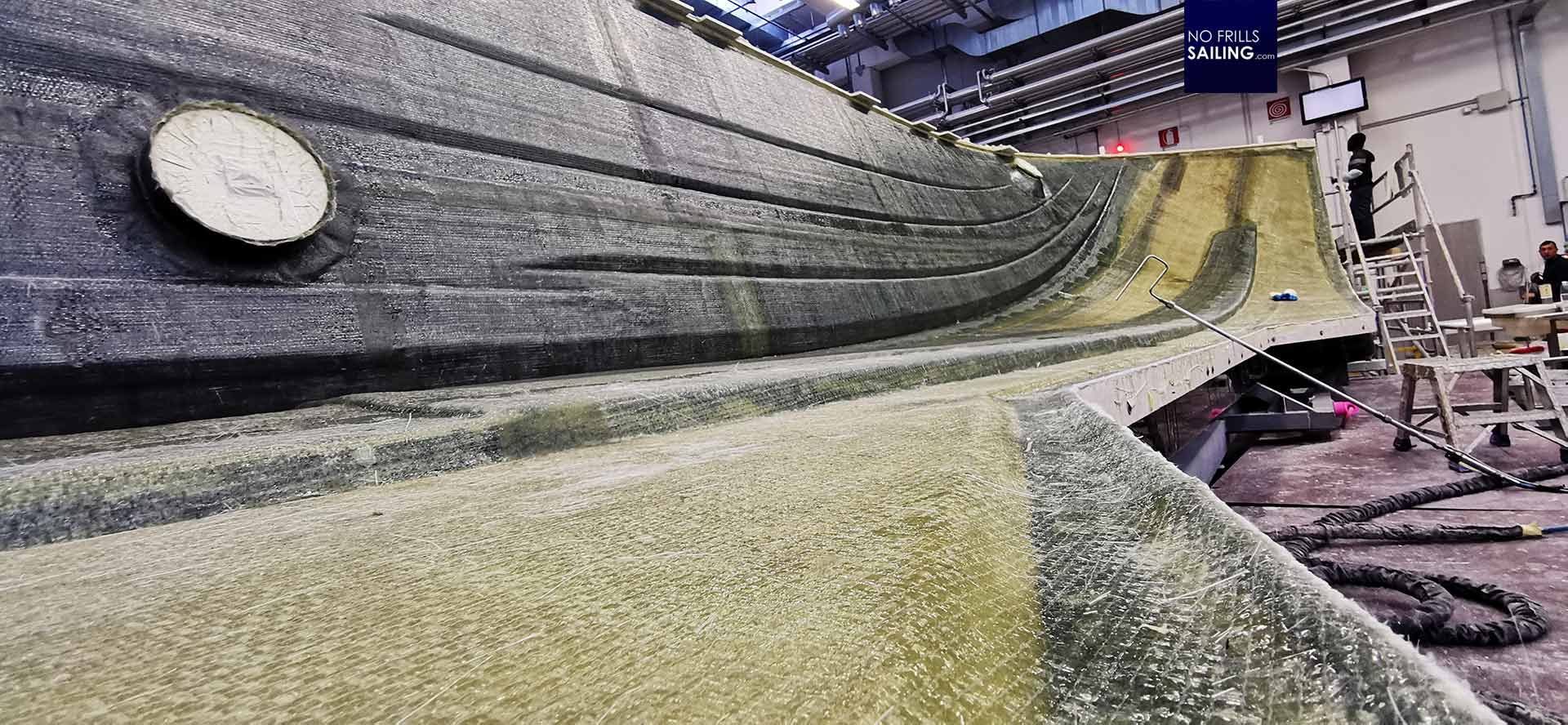

Anyway, as we roamed the large production facility where the +50 footers are made, we fund ourselves standing next to the impressive mold of their flagship, the amazing Cranchi 78 “Settantotto”. To be precise, we found ourselves next to one half of the mold actually – and our guests asked the question how in the world could a boat “just made out of plastic” be made so strong and stiff to withstand the stresses of the ocean? Well, that´s where the sandwich building technology comes into play.

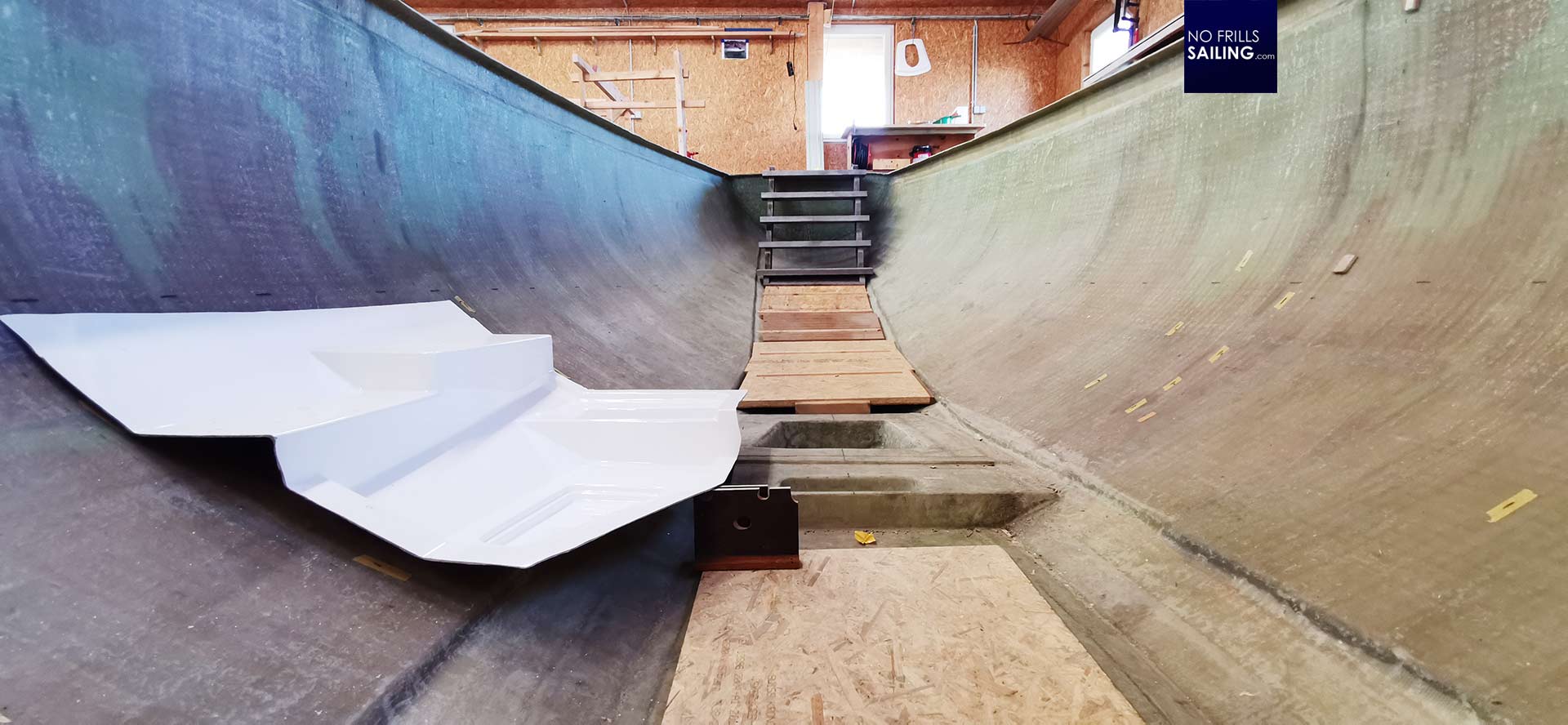

In the next hall, one of the 78´s half-molds had already been filled with the laminated hull. We could clearly see the thickness of the hull, but also identify areas of different colors. The darker areas indicated either massive laminates of glassfiber-mattrasses and resin or – as it is the case with Cranchi – Carbon-fiber reinforced massively laminated parts. The lighter colors are a sign for sandwich. Sandwich sounds familiar … and it indeed is what you think of it.

Sandwich laminates in boatbuilding

Basically, having a thin layer of a few glassfiber-blankets, encapsulating a “core” material, capped by another layer of glassfiber-resin makes a literal “plastic sandwich”. It provides a perfect combination of stiffness and lightweight properties. So for parts of the hull where no massively structural integrity is imperative, sandwich structures are the way to go to make a stiff and light part of this hull. You can easily identify sandwich parts in your boat (unless not painted over) because it looks checkered. Just like in my own new boat, the Omega 42:

Sandwich lamination is around for many decades in boatbuilding. Don´t be fooled by over-ambitioned marketing promising some breakthrough technology, making a boat stiffer and lighter by utilizing this technique is common sense and used for almost every boat. But there are of course major differences in the sandwiches, starting with a huge variety of materials. Basically, there are two main options.

Divini… what?

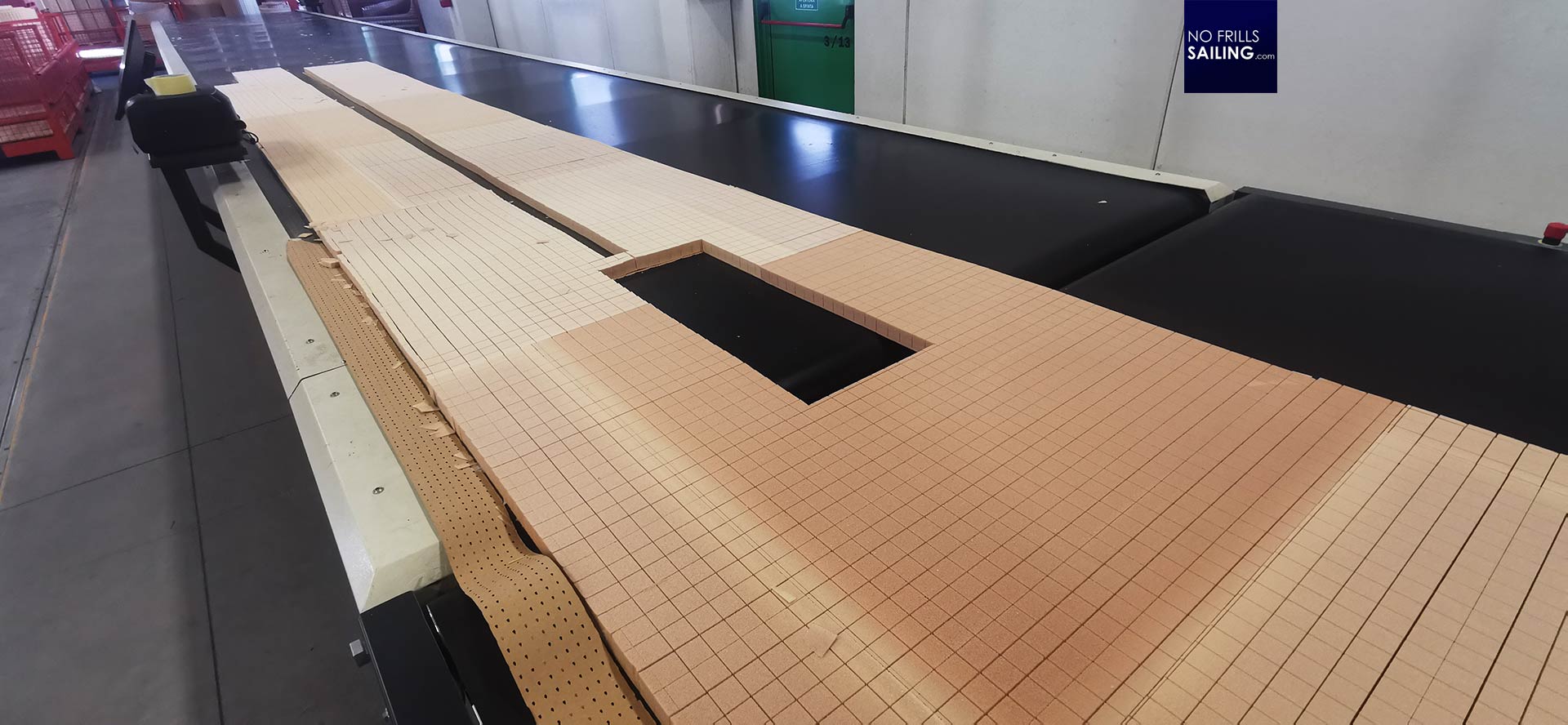

The sandwich core is a mattress (mostly a thin PVC gaze) onto which cubes cut to approximately 2 by 2 centimeters are glued. This cubical structure has two reasons: First, by that, the core can be bent so that it can easily take on any rounded shape of the hull or deck areas. Secondly, later in lamination (or infusion/injection), the resin will be soaking the core material and harden. The narrow thin blank areas between the cubes are filled with a solid hard glass barrier, making it impossible for water to go from cube to cube. This will be important.

Material-wise, there are two core substances in use: Synthetic hard foam, mostly made of PVC – you might have heard the term “Divinicell” – and Balsa. The synthetic core material has some nice properties which make it the first choice in high-grade boats, high performance-yachts and upper-priced boats. It provides a consistent material quality and can be produced in dozens of varieties with different properties.

Balsa core is the most common sandwich material in production boats and yachts which do not necessarily need to be trimmed to absolute lightweight perfection. Balsa is a natural material, meaning it is sustainable and, other than PVC core, its production and utilization does not produce any harmful fumes nor waste. But, as everything, it has its downsides too: When getting wet (by a ramming or something), Balsa will rot away, seriously damaging the boat´s structural integrity. This is know as hulls becoming “soft”. I´ve had this too in my first boat, the King´s Cruiser 33. Now, back to Lago di Como …

Cutting the sandwich blankets

At Cranchi PVC-core foam sandwich is used. As being a high quality boatbuilder making these huge yachts, a prcise manufacturing process is imperative. Cutting the foam mattrasses therefore cannot be done by hand. For this part of the production, automation is the solution. The shipyard therefore has a dedicated workshop with two huge cutting machines, which I found particularly interesting.

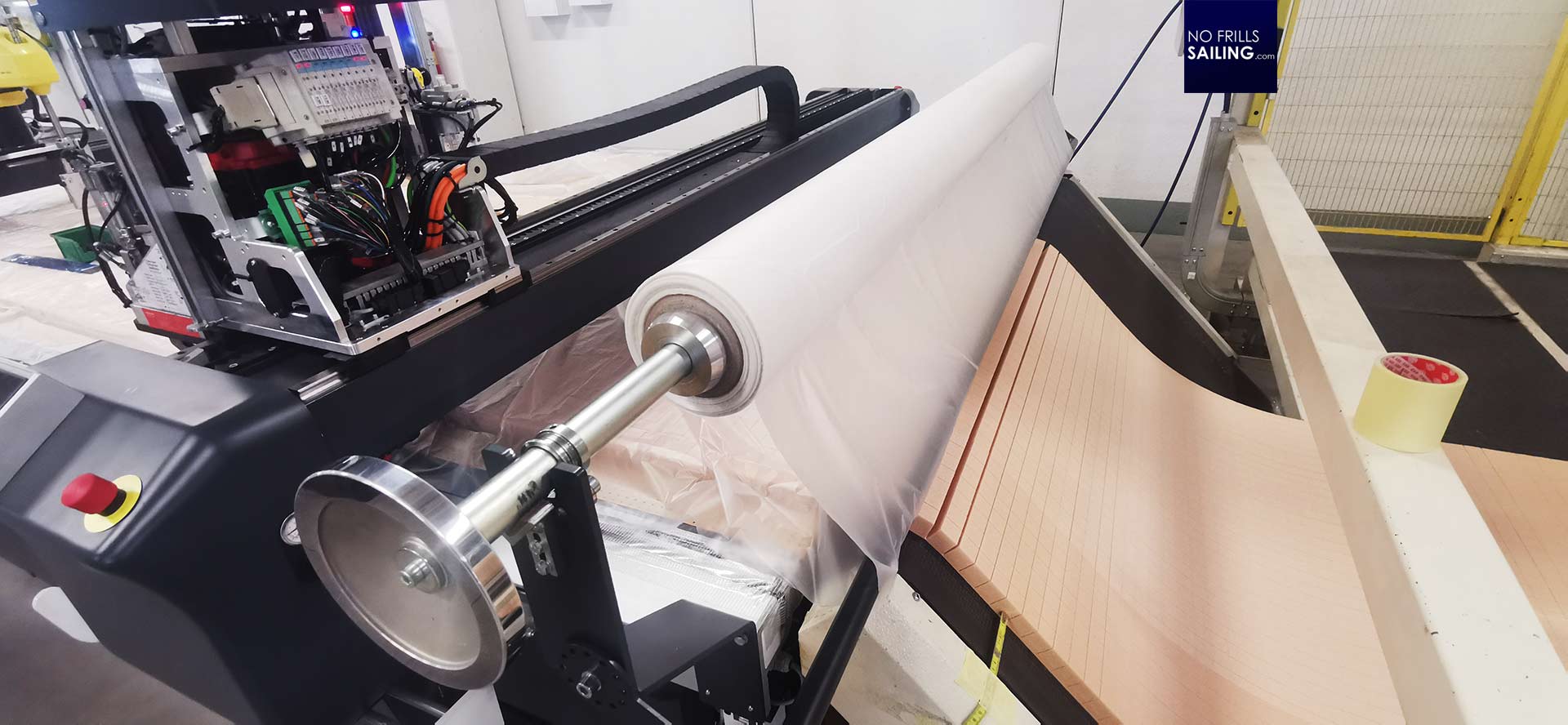

Basically, these machines can cut any material, from the thin GRP-garments to thick wooden boards and of course also the foam core mattrasses. For that, the huge coil or raw foam material is put on a roll and fed into the machine. A program with the cutting pattern is put into the machine´s computer and a worker presses the “Start”-button.

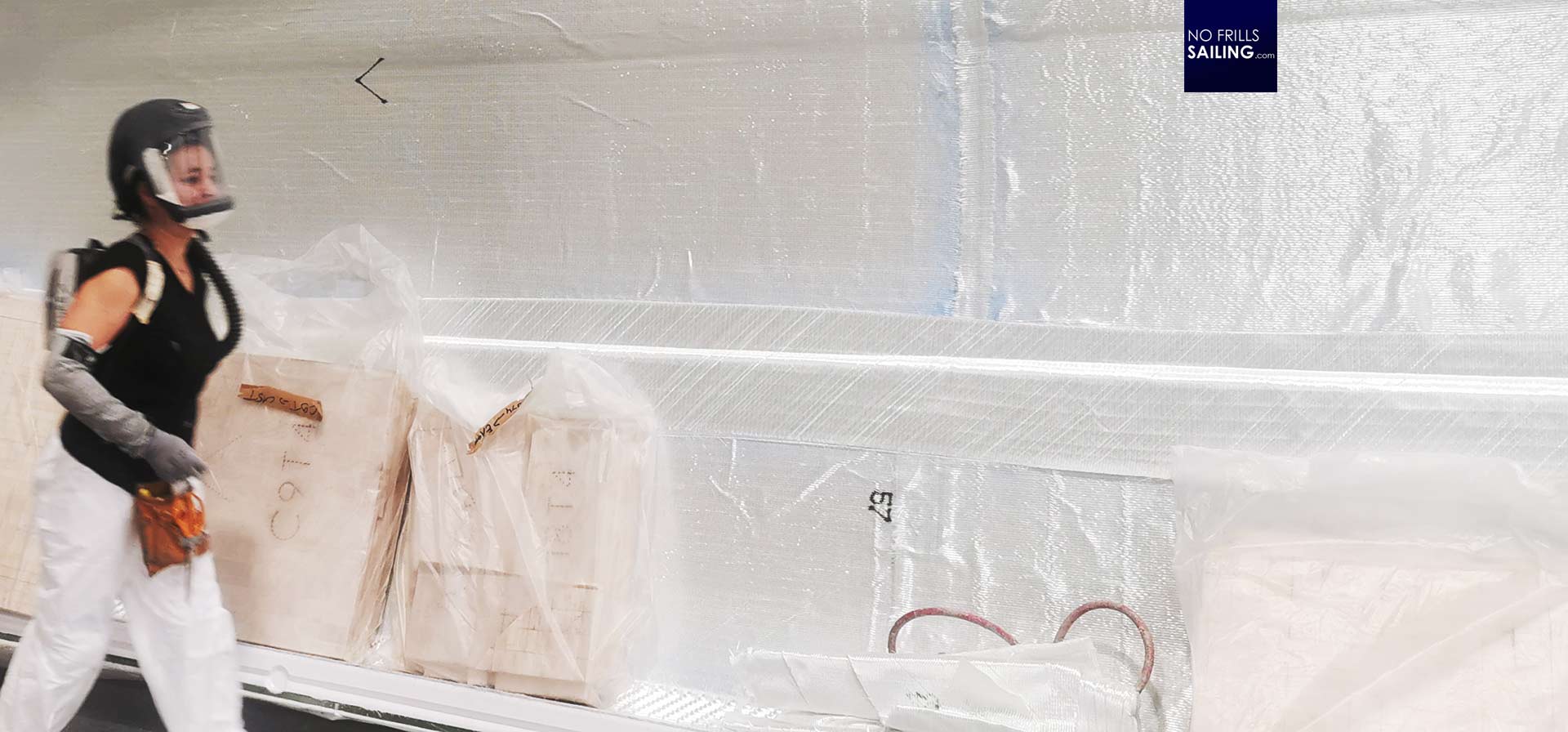

Cutting PVC-foam core will produce dust, bigger and smaller particles, as well as offcut that can pollute the air and plug the machine. To prevent this, another coil with some plastic wrap is fed into machine to make a “cover” during the cutting process. In this, no parts, bigger or smaller, can fly off the cutting table, ensuring a clean process.

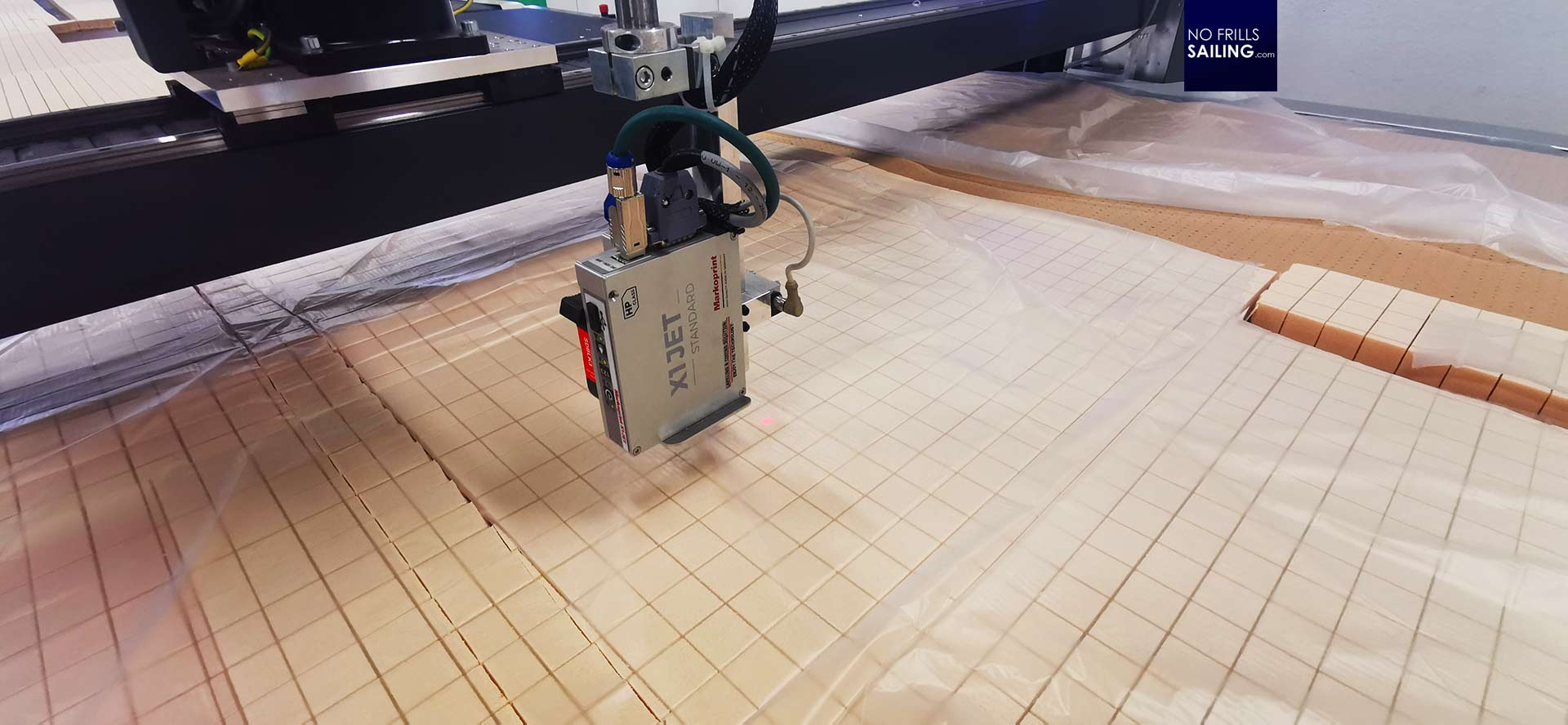

The cutter itself is a multi-tool that can be equipped with multiple cutting devices depending on the material that is to be treated. Bsically, it is a huge plotter that is hovering overhead of the material, placing the cuts according to the program. The size of the machine is enormous: This particular foam core mattress is not wider than around 1.50 meters, the maximum width this machine can treat is around three meters, which is pretty impressive.

The foam core mattress is fed underneath the cutter by a huge conveyer, slowly pushing the core through. Taking into account that the hull length of their flagship is little over 25 meters, this means that the core segments to be cut are also about that length. In this, the worktop after passing the cutter, is accordingly some 25 to 30 meters long.

The readily cut segments end up on this worktop where the plastic foil is removed, offcut parts and dust is taken away and vacuumed. The workers can now do a quality check to make sure that the parts have a perfect fit in production. Remember the picture of the hull mold: The forms and shapes of a motoryacht are very complicated to produce. Intricate design is a huge challenge: This machine is able to produce them with absolute accuracy.

After the quality check by another worker, the foam mattrasses are coiled up again, marked and put in a pushcart to be brought to the production hall. Imagine being here as a customer, taking the factory tour and seeing a cart with those parts, a sticker on it with your name? For me this is always very impressive. Almost like being present at one´s own conception: The nuclei of a future yacht, parts which will never be visible anymore, but which are making up the essence and very structure of the boat. Impressive.

Making a sandwich boat hull

So, how is a sandwich laminate produced then? Irrespective of the material used, there are basically two kinds of producing a sandwich laminate. It can either be done by hand or, preferably, with the help of a vacuum. Hand laminating is most commonly utilized. As seen for example during a customer´s factory tour at Excess, this requires a lot of human workforce and those have to be very skilled.

The sandwich core parts are put on the first (outer) layers of glassfiber/resin-mats, soaked in resin and then covered with the second layers of GRP, which will make a bond. This has to be done very carefully and attentive, because we do not want to have any air bubbles within the laminate. An argument pro vacuum infusion is the exclusion of air bubbles and irregularities as far as possible. I´ve done a separate article on vacuum infusion during a visit at the X-Yachts shipyard in Denmark.

Next to the vacuum infusion, where the resin is infused and “sucked” into the dry laminate-layers of glassfiber and sandwich, vacuum injection is almost the same procedure. The resin is injected into the dry layup that is enclosed by a male and female mold, thus creating two “nice” A-sides whereas infused parts just have one A-side. Vacuum infused/injected sandwiches generally have less weight and are considerably thinner, but have also some debatable long-term degradation effects. There are many people who fancy Balsa end grain as core material over PVC or synthetic foam products.

Environmental aspects

This pro-Balsa faction states that – provided the Balsa core material is made out of the end grain – has basically the same features as synthetic material without any hazardous side effects. Many GRP boats are degrading, are still sunk fraudulently or end up being dismantled slowly by the work of natural forces. This is releasing microscopic parts of the foam core material into the Oceans, which is a problem indeed. Also, Balsa is sustainable, no hazardous fumes are released when producing and processing it. Well, there´s no black and white, as usual.

In the Cranchi shipyard we show our customers one big part of a deck with a considerate amount of foam core material. Also, at some parts, the shipyard mixed the available core materials as to a point where massive wooden parts are used for structural strength on exposed parts. As for my boat, the Omega 42 is also made in a sandwich construction.

Most of the underside, the part where the keel will be attached and basically part that in old times was called the keelson is massive GRP, the hull itself is a Balsa core sandwich construction, laminated in hand-application. Which way your boat has been constructed howsoever, by skilled craftsmen or aided by huge automatic robots, which of them core materials are used – I hope your boat will have all the strength and longevity “to the core”.

You might as well find these related articles interesting to read:

Vacuum infusion in boat building – at X-Yachts

A mountain of plastic: About the new boat transport wrapping

Is sustainable boatbuilding possible?