If you haven´t read it yet, you might start with Parts 1 and 2 of the #biscaysailing series by clicking here.

We had left Muxia marina a day before as the sun went up so brightly on that second day at sea. A glorious day, I reckoned, when I went to the cockpit and saw the Spanish flag proudly waving in the sky. I decided to let it there until we would have reached Brittany at the other end of the Gulf of Biscay. Before us the distance of some 450 to 500 miles, depending on the course and the weather, 4 to 5 days, as we had calculated so many times.

The boat was rolling heavily. In fact, the state of the ocean did not reflect the innocent harmlessness of the skies: We had waves of some 1.5 metres in height, coming in from virtually every angle. Shortly after clearing sight of land. It was awful and it got worse by the minute. Biscay, it truly had us now and the dance was about to begin. I dashed down – notwithstanding the fact that I did still have watch below – and came up again.

Sailing seasick in boiling waters

The Bavaria 37 Cruiser FREE WILLY, an 11.45 metre long boat built some 15 years ago, began to shake more and more, every step was demanding a high focused mind and a strong grip to a handle or something. During the night the crew decided to have all canvas taken out so the yacht became stressed by the pressure in the rigging. Problem was that wind eased so much – to mere 8 to 10 knots true – that the tiny boat became more and more lost in the boiling seas.

Skipper decided to take in the Genoa but had the main sail out full. We started the engine which apparently turned out to be the only way to cope with the crossfire of the incoming waves. “I think that’s the continental shelf.”, I began to think loudly. The strong Atlantic waves, having had the time to roll onto Europe´s coasts for three thousand miles unhindered in a 3.000 to 4.000 metres deep ocean, are now forced to a water as shallow as 300 metres. The breathtaking energy is compressed, focused and bursts upwards causing the area to “boil”. It was a fascinating view, but: “Strange enough, I always wanted to see this but somehow I just thought of these conditions to occur more northwards.” But of course, the shelf is also present off Spain.

Sailing under engine power is stressful. The boat roared and squeaked, making barely 4 knots over ground. The mainsail was filled with air but failed to stabilize the boat. So we went from 20 degrees on on side to 20 degrees of the other side. We rolled heavily and it lasted the whole second day. The distance we had to bridge to let behind us these violent, whisked water, was about 40 miles or so and when the sun was about to go down the sea had apparently calmed down a lot. It was my watch when I took out the Genoa, switched off the engine and made a present to my crew who enjoyed the absence of the loud Diese-humming, nodding off into a relaxing dream.

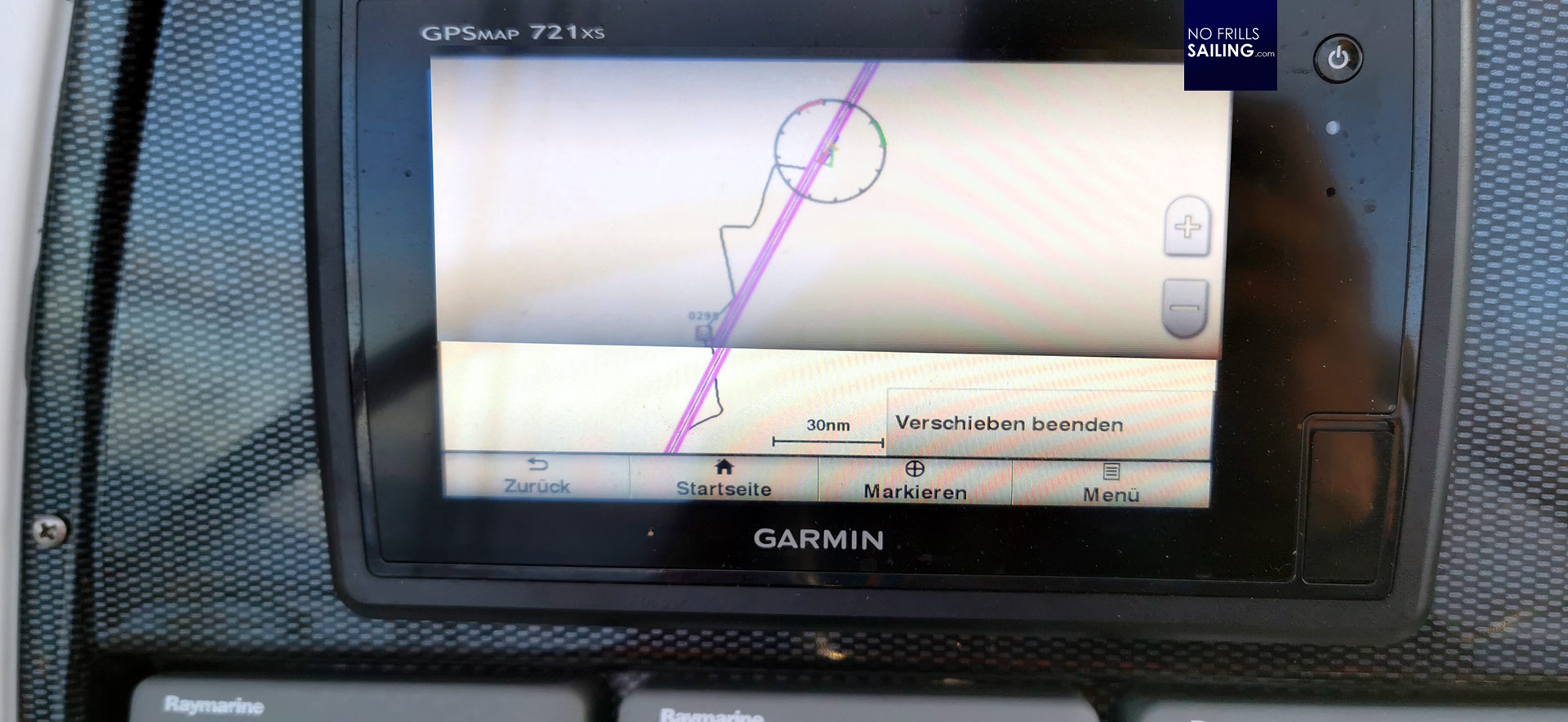

We were able to sail – and this not slow – but with one downside: Wind blew directly from the direction we were heading into: 035 degrees, course directly to the northwestern corner of France. So we had to tack. As joyful and fun it was to have out all of our canvas at last and the boat cutting surprisingly fast through the waves – 5.5 zo 6 knots SOG – the depressing it was to see our track zig-zagging over the general route. Nearing oneself on a tack towards the destination means a tripling of time and distance: After half a day and the eighth tack a light depression became apparent in the faces of our skipper.

When yesterday´s worry lines in his face had been caused by the calculation of fuel consumption, he today was worrying about the overall time we´d need to reach our destination. “If conditions do not change it could take us not 5 but 15 days to cross the Biscay”, he said. Well, last weather forecast I received some 20 miles off the Spanish coast by a still miraculously flawless working LTE-grade internet connection (hats off to Movistar!) predicted a change of winds to the East by … now. If this would happen, we could sail at least for two days on a broad reach port side tack. “We must sail for at least 2 days otherwise fuel won´t last”, I didn´t forget about Skipper´s equation.

Modus operandi: Shift system on multi-day trips

And so it did. I don´t know exactly when but I remember just when I came up during my daylight shift Skipper looked into my face and said: “Wind shifts constantly. I am changing course altogether with it, 10 degrees more and we are directly on course towards the Channel.” He smiled. Great news! So I took over the helm and over the first of my three hours of time the boat finally was put on 035 degrees course, full canvassed making some 5.5 knots over ground. Great stuff!

As we sailed into the dawn conditions aboard had already improved significantly. Due to the fact that the boat was now on a stable course and the old-school hull shape of our cruiser even the upwind point of sail (we hadn´t reached the broad reach state of sails) we did have a heeling of course but otherwise the boat was nicely cutting the seas. Sleeping became possible again and no other sound than the orchestra of water and bubbles and spray sliding all along the hull was to be heard.

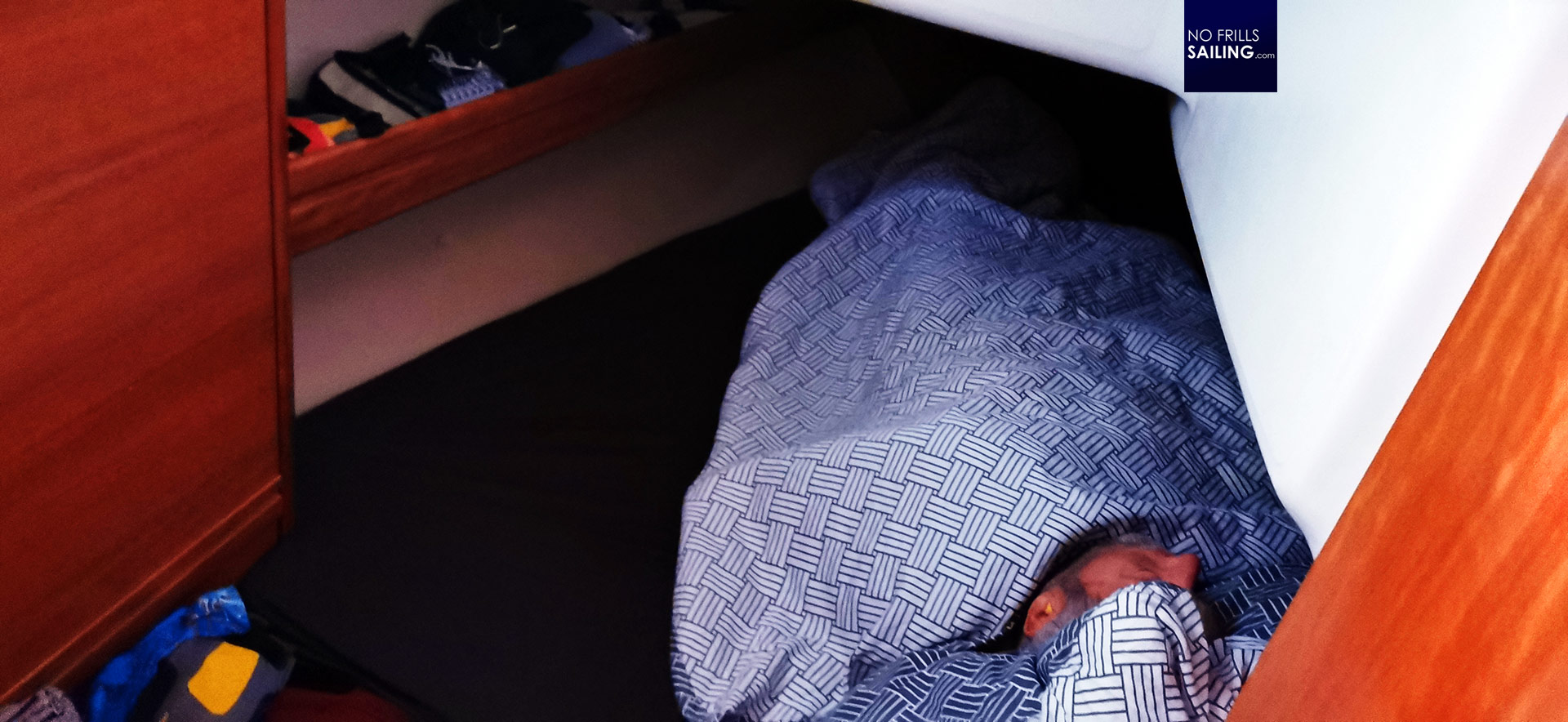

Well, not for all: As it is “good tradition” of my body on longer trips with so much movement in the boat I became seasick again. I know this phenomenon since my last big offshore trip to the Canary Islands when I suffered for straight three days and so I knew that “my” kind of seasickness won´t become so severe that vomiting would be a thing but nevertheless, it was annoying. Staying down below was a strain, my stomach turned upside down. Only by laying in my bunk it became bearable. Being up in the cockpit was okay, symptoms took a back seat, but it worsened when no horizon was observable during nighttime. I had to hang in there and just wait for the fetch to end.

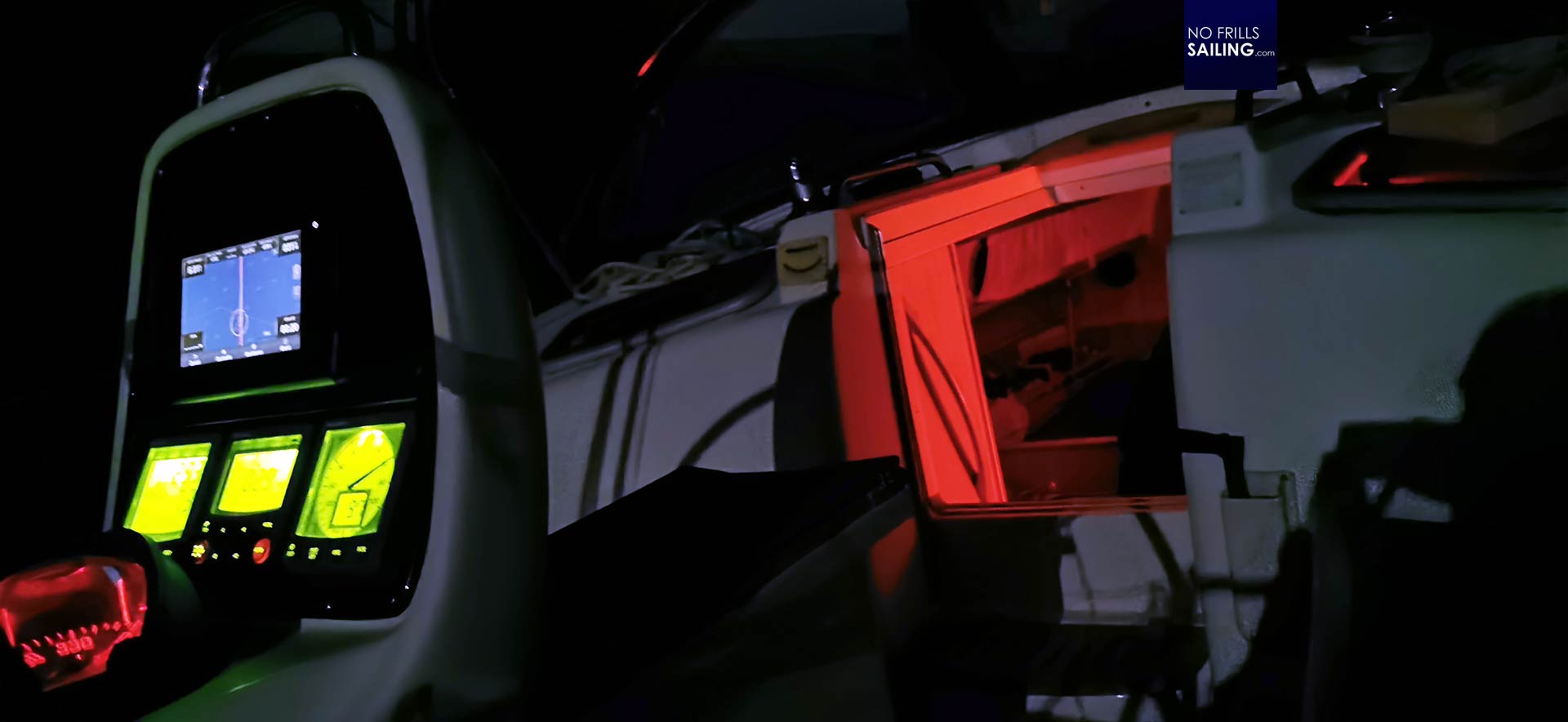

Mostly, during my watches in the night, I put myself into the horizontal on the benches and tried to kill time. Every 10 or 15 minutes I would then get up – not without a certain old man´s moan – take a look into the sails trim and the instruments: Checking for wind speed and wind direction on the one hand and for our boat´s course and distance made good on the round on the other hand. I would then take a sharp lookout 360 degrees around the yacht if there were any boats or objects (which was completely useless given the darkness). Repeating this cycle all through my watch of three hours until being relieved, faltering down into my cabin, taking off the oilskin and falling into my sleeping bag.

Rasmus, the mighty God of the Winds, was in favour of us and made the present to us of this constant, warm wind blowing from the Eastern landmass of France, bringing hot and dry air and propelling the boat with reliability. Our days became less and less challenging sailing-wise but a turned into a test of human endurance. Our normal day was dominated by the shifts. Three hours on, that meant being in charge of the helm, responsible for the boat; and the six hours off – time to sleeps, recover and replenish.

This was repeated three times a day meaning that at least one shift had to be sit through in broad daylight, two shifts in the night or in the twilight hours. The first day it was no problem since Adrenalin was up and high and we were full of joy that we had been finally gone out to the seas. The second day it became harder and – at least with me, maybe also because of the seasickness – on the third day it was the hardest. Especially the shifts at night became very demanding.

Aside from the stresses of the 24-hours-sailing, we adapted to the life at sea. My seasickness disappeared as fast at it showed up 24 hours earlier. It now did not pose a problem to spend time below deck: preparing food, being on the ceramics or just being down below was now possible without any symptoms in my stomach. Apparently, neither the Skipper nor Markus, my sailing made, showed any symptoms of seasickness but I observed a certain change in Markus´ behaviour over the course of all the changes of guard. He became more silent too and we all seemed to reduce our talking, our actions, every single movement to the necessary, not wasting any energy nor any minute. Interestingly enough, we adapted to the 3 on 6 off-routine quickly – but I observed another interesting thing.

Daylight highs and human biorythm

When at sea, every movement is dictated by the movement of the boat. Take those three metres from the galley to the table: They are a well-balanced ballet of calculated steps put into the rhythm of the waves and the movement of the boat. Even taking a dump on the toilet is concerted to the seas, waves dictating pressure and relaxation. What works in the smallest also has it influence on the biggest: When sailing a multi-days trip, you very much intimately get to know your own bio-rhythm. At least, I did.

During daylight, even after a tiring dog´s watch, I used to get up after one or two hours (of them six) and be in the cockpit. Mostly Markus was then preparing a meal, sometimes the skipper swinged the cook´s scoop. We spent some hours up on deck, chatting and talking, eating the meal, having a fresh apple or a cup of wonderfully crafted onboard coffee. Our bodies were up and running, no tiredness at all. Mood was up and spirits as high as can be.

That was when our bio-rhythm was up. Daylight brough energy, just like a flower turning its blossom up and into the sun. We would meet in the cockpit and discuss the progress. “We are blessed!”, our Skipper used to say: The third day on port side tack, winds still up and the boat making steady progress. We had passed the midway mark of the journey through the Gulf of Biscay and with it the threshold of our Diesel-range. From that moment on, the Skipper became apparently more relaxed being able to cross off that looming potential problem from his list. But what was so nice during daylight became increasingly hard during the nighttime.

Exhaustion builds up

Of course we did not have cell phone connection but GPS and Google Maps worked. I checked our position on my smartphone every watch and took a screenshot. Even knowing that I would take a close look onto the – much more precice – data on the ship´s plotter, I kind of enjoyed scrolling through the screenshots. We now came closer and closer to the land by the hour – but as well did fatigue build up ever so slightly.

I developed a technique to make my night-shifts more bearable. Adopting a mind-strategy I´ve developed back in the days when I used to be a roadbike-racer and Marathon-runner, I began to better cope with being constantly tired and even reverse the mood, raising my grade of vigilance and awareness when responsible for helming the yacht.

This strategy basically can be described as “cutting the hours”. In essence, instead of all the time thinking oft he full three hours which are ahead of me now when taking over the helm, I “cut” the watch and just looked to the first hour: By setting up goals and milestones to think of you “forget” to see the whole picture but focus on the next milestone. That makes it bearable. For example, in the first of the three hours, I set up two milestones: Eating an apple or a chocolate bar after 30 minutes and going down to switch off the heating (yepp, Skipper, whom I relieved from duty would always turn up the Diesel heating and I agreed to switch it off after 60 minutes).

So, I would not count three hours, but “just 25 minutes till I can eat my apple”. This sounds far better that “oh, 2 hours 45 minutes till watch is over”, doesn´t it? I remember that this strategy worked very, very well for me running a Marathon and it began to work out just fine during the worst watches, 0100 to 0400 in complete darkness. During the second hour I would focus on seamanship: Sails trim after 1h20m and checking distance to waypoint (set right at France´s northwestern corner) at 2h45m. The best was the third hour which I broke down to just 45 minutes: “15 to full!” was the sentence with which I used to wake up Markus. Looking forward in pleasant anticipation for him getting ready, taking a dump, brushing his teeth, getting dressed and winding his way up to the cockpit made me forget about the last 15 minutes of my watch. So, by setting up 5 milestones I was able to “shorten” the time experienced and thus easing the stresses of a nightwatch considerably.

Apart from this occupation with myself, around our boat the Gulf of Biscay was surprisingly calm. Just off Spain we´ve had some fishermen in the darkness, most of then with AIS-signals transmitting, a few without. No problem, neither ship came nearer. Closing in on France our Skipper upon relieving him from duty talked about a notorious cruise ship directly closing in on our course he had to call via VHF. Apart from that, the Biscay was calm, quiet, no traffic at all.

A weak point: Nutrition underway

Along the ever building fatigue another point became apparent during the trip through the Biscay: Eating and replenishing our body reserves with nutrition was a real downside from my point of view. This sounds especially odd since Markus – from day one – was a great ship´s cook and undertook loads of efforts to deliver sumptuous delights of delicious foods on a daily basis. I gues, now one week after the trip, his ambition and glowing enthusiasm was the reason for this downside.

I seriously began to think about this thing going wrong when I catched myself one morning devouring a can of baked beans. Cold baked beans, spooned right out of the can. They tasted fairly good but made me re-think the food-planning of our trip. Roughly two weeks before casting off, Markus sent an email to Skipper and me with a suggested menu. This list contained delicacies like “Rolls of Zucchini with ham in Tomato-Sauce”, “Old-fashioned stew of Beans and minced meat”, “Home made Lasagna” or “Linguine al oglio”. Well, I did not know Markus beforehand and as he apparently loved cooking I gave up all of my own ambitions to cook and kind of silently transferred the oversight on provisions and meals to Markus.

I worked for us: Markus seemed happy spending hours in the galley down below, chopping fresh veggies, pre-cooking sauces, frying meat and putting rich filled casseroles to the hot oven – later he would serve huge bowls of hot steaming delights and we would tune into a chorus of praise for his cooking abilities. It worked so nicely that his meals became the one and only meal of the day. Both Skipper and myself completely forgot that a 24-hour-day at least demands one breakfast, one lunch, one dinner and a midnight snack.

So, instead of planning ahead in this holistic way, we concentrated on this one glorious meal prepared by Markus and did shop just “by the way”. We had no scheduled, regular breakfast – although cereals and milk, eggs and ham had been in our stores – we had no dinner, although enough provisions had been taken on. So, instead, I cracked open a cold can of baked beans in a seizure of hunger, devoured three or four chocolate cereal bars at night and forced myself to collywobblingly wait for Markus´s daily delight.

Same goes for the drinks: I am not a good drinker anyway but I guess it was the lack of constant “rich” nutrition that made me drink too much Coke, as sugar is a fast and cheap energy source. As a learning from this trip I will definitely keep a closer eye on menu planning and regular meals for the crew pre-planned on my next trip. Nevertheless, thanks to Markus´ culinary art we never really fell short of food or nutrition, especially myself: I regularly spooned the lunch´s leftovers at 2 o´clock a.m..

A tricky, long & hungry Brest approach

It was on the second or third day of the Biscay-crossing that it became apparent that the prevailing wind would be suiting us very much and blow us all the way up North without a change in weather. Lucky us: The Gulf of Biscay turned out to be very in favour of us, delivering best sailing weather. No storms, no gusts, no rain – no nothing! All I had read about the gruesome infamous Gulf of Biscay turned out to be non-existant. At least for us on this very trip. We were very thankful. Skipper´s original plan was to round Brittany, enter the English Channel and make landfall in the French port of Roscoff. I calculated distance and time and told the crew on one of our culinary meetings in the cockpit why going to Roscoff wasn´t a good idea in my mind.

“First of all”, I began: “we will be at sea for six, possibly seven days in one row and exhaustion already has been building up. Secondly, we have am Easterly blowing which means going east in the Channel would mean to tack towards Roscoff – certainly prolonging time and distance, worsened by the effects of the strong tidal streams in the Channel.” I suggested to go to Brest, saving some 60 miles and certainly one if not two days. Both agreed immediately.

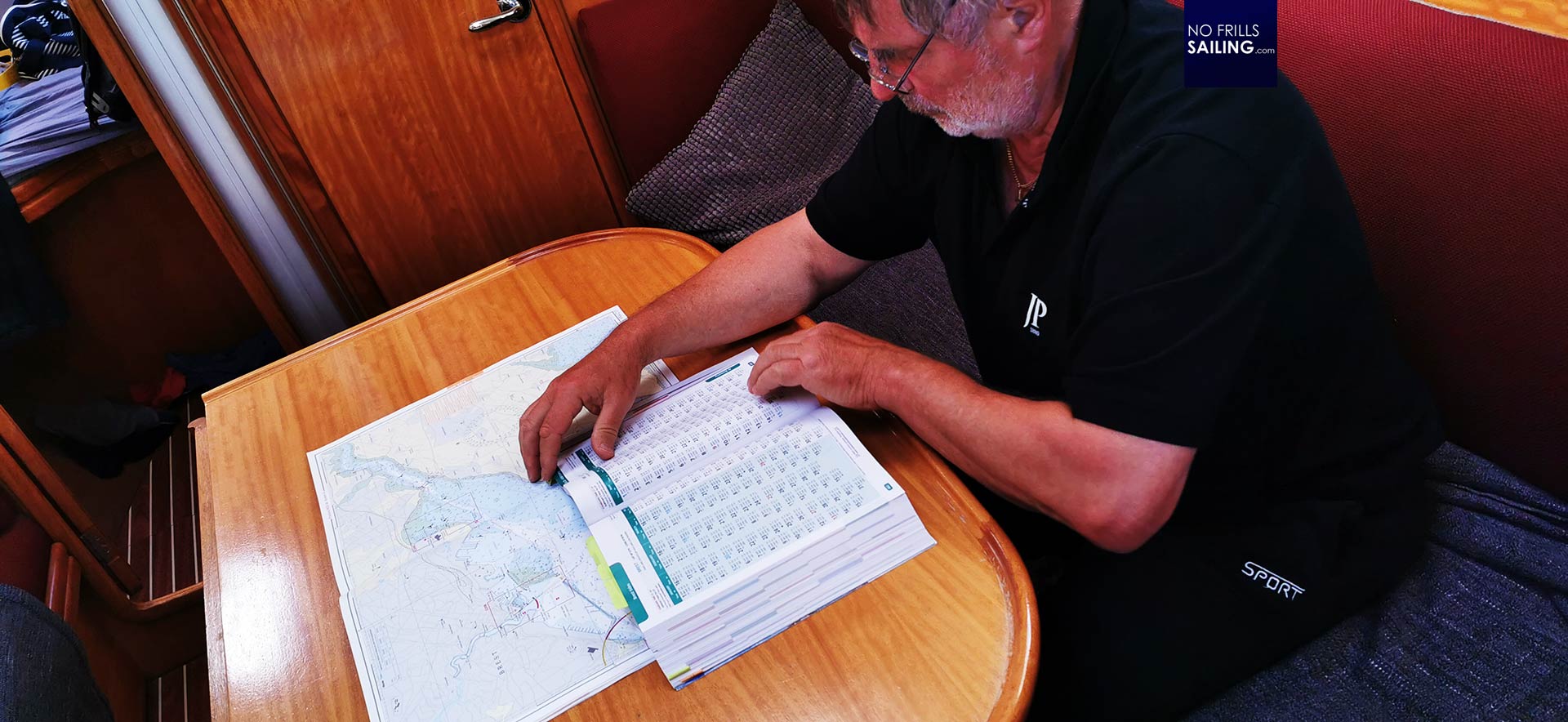

Brest, the old Navy base, is also prone to tidal effects and so Skipper and me consulted Reed´s almanac, the naval charts and our plotter to familiarize with the new destination. Now, on the fourth day, just 30 miles off Brest´s approach buoy, spirits were up again: A normal effect on seagoing people. The harbinger of land, birds and insects, began to visit our boat more frequently and just as we were as near as 28 miles to France´s coast the wind finally died. Thank you, Rasmus: Four days of favourable blowing, what a lucky bunch of people we were!

We couldn´t think of sleep now. Tired as we were, we all met in the cockpit as finally land came into sight. I was so hungry. So I began to talk about food: “What about old-fashioned Roulades … with potato dumplings and red cabbage?” The others joined in: „Or smoked pork chops „Kassel“-style with mashed potatoes and Sauerkraut?!” Saliva began to flow. „Schnitzel Vienna-style with cucumber salad and potatoes …“ Now running with engine again and having some 23 miles still ahead, talking about traditional German food was topic of the day. “I have it”, I suddenly said: „Boiled eggs in mustard sauce!” Both lokked at me, dribbeling, hungry … oh yeah, boiled eggs!

Brest approach is tricky, especially when done first time and in a pitch black night. We crossed the bay passed the rocks of Ile de Sein and found our way through the blinking chaos of buoys and fairways. I was at the helm all the time, bladder filled to burst, empty stomach. Just thinking about one single thing: Boiled eggs in mustard sauce …

A city with no city center: Brest

We tied up the boat at 03.30 a.m. the next day in Marina du Chateau, Brest´s prime harbor for sailboats. After congratulating each other for this 4.5 days-sailing experience crossing the Bay of Biscay, traversing one of the most notorious areas of the world without any harm or hardship, we fell into our bunks and slept until 10 in the morning. Biorhythm and the mouthwatering scent of freshly brewed coffee made me get up after just 5 hours of deep, relaxing sleep.

“Bonjour a France“, the nice people of the harbor´s office welcomed us as I paid for the demurrage and returned to the boat. We decided to not only stay here this day but spend another full day in Brest to regenerate. Our log listed a sailed distance of exactly 499.88 miles since Muxia, confirming our plans one week ago. Yet, in all the lush atmosphere, I still had one thing to cross off the list …

I cooked the eggs and served a full bowl of eggs in mustard-sauce all to the excitement of my crew mates, who praised this German-food, sitting in the Brest sun, enjoying a cold Portuguese beer and not having to grab hold to the boat for the first time in days due to no movement at all. We felt great – as I am a France-loving guy, I immediately felt at home listening to this wonderful language.

As a German, befriended with some of the actors who played in my favourite movie of all times, “Das Boot” I naturally was keen on seeing the U-Boat bunkers of Brest which had been the biggest bunkers built in World War 2. Unfortunately I couldn´t visit it but had to picture it from afar, but we soon set off to discover the City of Brest. My internet research brought to light a website which stated: “What to see in a City with no city center?” Walking up the – very steep (!) – hill to town we acknowledged that indeed Brest lacks a distinct center. On the other hand, we enjoyed so much the lively, unique, still working and bristling harbour of Brest.

I was fascinated by the magnitude of the tide apparent in Brest. Roughly every 6 hours the marina´s pontoons swam up to a level some 6 metres higher than during low water. Virtually every time I came up on deck the marina looked different. Strolling around in the harbor (looking for boats), replenishing food and drinks aboard and talking to loved ones at home we spent the next day. Weather unfortunately became less pleasant with cold fog and some rain and so faster than expected we began to talk about leaving again.

Next leg up: English Channel

A last time we enjoyed the good food – unfortunately not in a fish-restaurant at the harbor because it was the day when all were closed – but the Burgers served at the marina´s restaurant were as delicious as Burgers can be. We talked about the coming big thing: The English Channel. As the busiest seaway of the world with some 500 ships passing through on a daily basis, the Channel definitely would become the complete opposite of what we had just experienced in the Gulf of Biscay. I saw it coming: Watches would change dramatically, lazy time adé.

Weather forecast promised a 15 knots wind which would come in from the West – perfect for a Channel-crossing at a running point of sail. “Imaging the Easterly would prevail and we´d have to tack through the procession of cargo ships, against the tides, dancing between the traffic separation schemes!”, I reckoned. It seemed that we could be lucky again, favoured by mighty Rasmus, with a wind that would suit best our route. I checked the tides: “Okay, just like in Porto, we will have to leave in the middle of the night …”

Well, that´s sailing with the tides: You have to go when water is falling. That said, the next high tide would occur at 0330 a.m. so after refilling the Diesel-tank we decided to go to bed early, just as the saying goes: “Nine o´clock is sailor´s midnight” and at 0200 my alarm clock set off. Clever enough we had prepared the coffee maker so that just minutes later a fresh, strong Espresso roared in the Bialetti.

It was pitch black outside as we gathered in the salon, finishing a second cup of coffee and somebody of us also finally opened the package of cereals to fill the stomach. Outside it was a fresh 17 degrees Celsius moist air. Nobody was awake – most of the yachtsmen have left a high tide before this one some twelve hours ago as we had still enjoyed the warmth of a sunny Brest day. Skipper and Markus again studied the fairway and did a last check on the weather.

Leaving Brest harbor is easy – you just pass the mighty breakwater and turn West. A very narrow sound of 2 miles length and a width less than a few hundred metres needs to be passed. Tidal streams of up to 5 knots may occur here so any skipper is well-advised to come with the flood and leave with low water stream. As we would do.

We finished our coffee, got dressed and dropped the lines at 0315, just as the tide turned. Rather than spending some time in Brest, maybe rent a bike and discover the surroundings, we left after one and a half days – too luring the prospect of having good winds in the channel, to pressing the schedule. Skipper must reach his new home port in Eastern Germany not later than August 29th and I had to be at home again at August 10th for the school enrollment of my son which I of course under no circumstances wanted to skip. How would traversing the English Channel be like? Busiest waterway in the world. Strong tides. Lots to look forward too. And I began to think that maybe this Channel-crossing might be the real adventure of the trip, surpassing that of the Biscay …

You may read all articles of the Biscay- and Channel-crossing by clicking on this hashtag #biscaysailing

Also interesting to read:

What makes a good skipper, Parts 1 and 2

Skipper´s essentials, all articles

The perfect boat for the long haul