I lately finished reading a quite interesting book. It is a wonderful mixture of the exciting journey into the history of naval charts and a rich collection of valuable information for sailors as well. I´d say, a perfect Christmas or birthday present, if you look for something to hand to a fellow celebrating sailor. “The Sea Chart” is a big-size 157 pages strong book by John Blake, first published in 2004.

That this book is something special is emphasized by the foreword. Nothing less than His Royal Highness, the Duke of York, wrote a wonderful epilogue to that book. He is pointing out that it was the tireless work of thousands of seamen, able cartographers and ingenious scientists who, over the course of hundreds of years, dared to sail into the great whiteness only to wrote down what they´d had come across. The very foundation for Empires, not the least the British Empire, was laid by seafarers who won their advantage by navigating safer and faster – enabled by naval charts.

From tacit knowledge and decisive benefits

I do not intend to spoil your wonderful experience reading this book. Or, let´s say, “experiencing” this book. Thus, it´s less reading and more seeing. The texts tell about the historic facts and setting, they do explain which steps in cartography had been done, but it is the wide variety of wonderfully arranged and selected charts themselves which makes the reader discovering the context and connecting the point.

In this, we get to know that the first “real” naval charts had been called “Portolans”. Those weren´t charts in our modern sense. A mere visualization of a coastline with some drawings which aren´t to size. Names of ports, cities, harbors all along. Together with notes about reefs, capes or other hazards. We learn that those Portolans weren´t necessarily public knowledge: Captains and navigators held them in their private possession, special and secret knowledge giving them decisive benefits and advantages over other Captains. Over other kingdoms as well. This knowledge was sought after fiercely, not unfrequently with military means.

Early naval charts and mariner´s superstitions

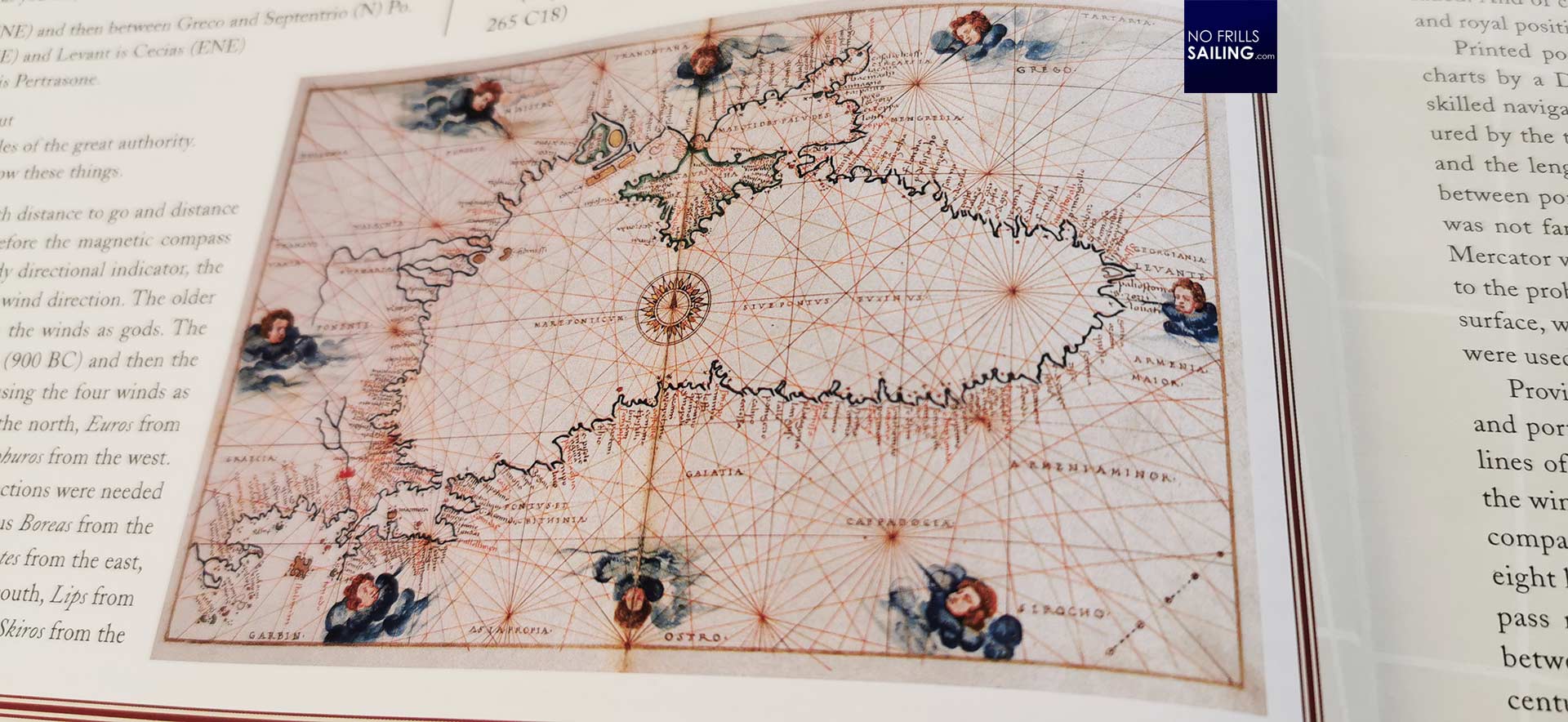

Early naval charts had been a mixture of knowledge, a lot of estimates and much more of superstitions and legends. You get to see many charts sporting a wild array of seaborne monsters or imaginary continents and islands. I also – at last! – got to know from this book where the term “rose” or “wind rose” is determined from.

Those ancient Portolans had not yet been aligned North-up. It was up to the artist. This changed a bit when those charts were garnished with wind roses. Mostly from the eight principal wind directions coming, those God of the Winds had been drawn grouped all around the area of the map. The winds then “blew” in their main directions (North, West, South and East) by means of four lines. Four further lines indicated the wind directions “in between”. Since each of them eight wind roses had eight more lines, this finally explained why older charts had been so wildly crisscrossed. Later, the wind roses were substituted by the rose of the compass and the wind directions disappeared, giving way to latitude and longitude lines.

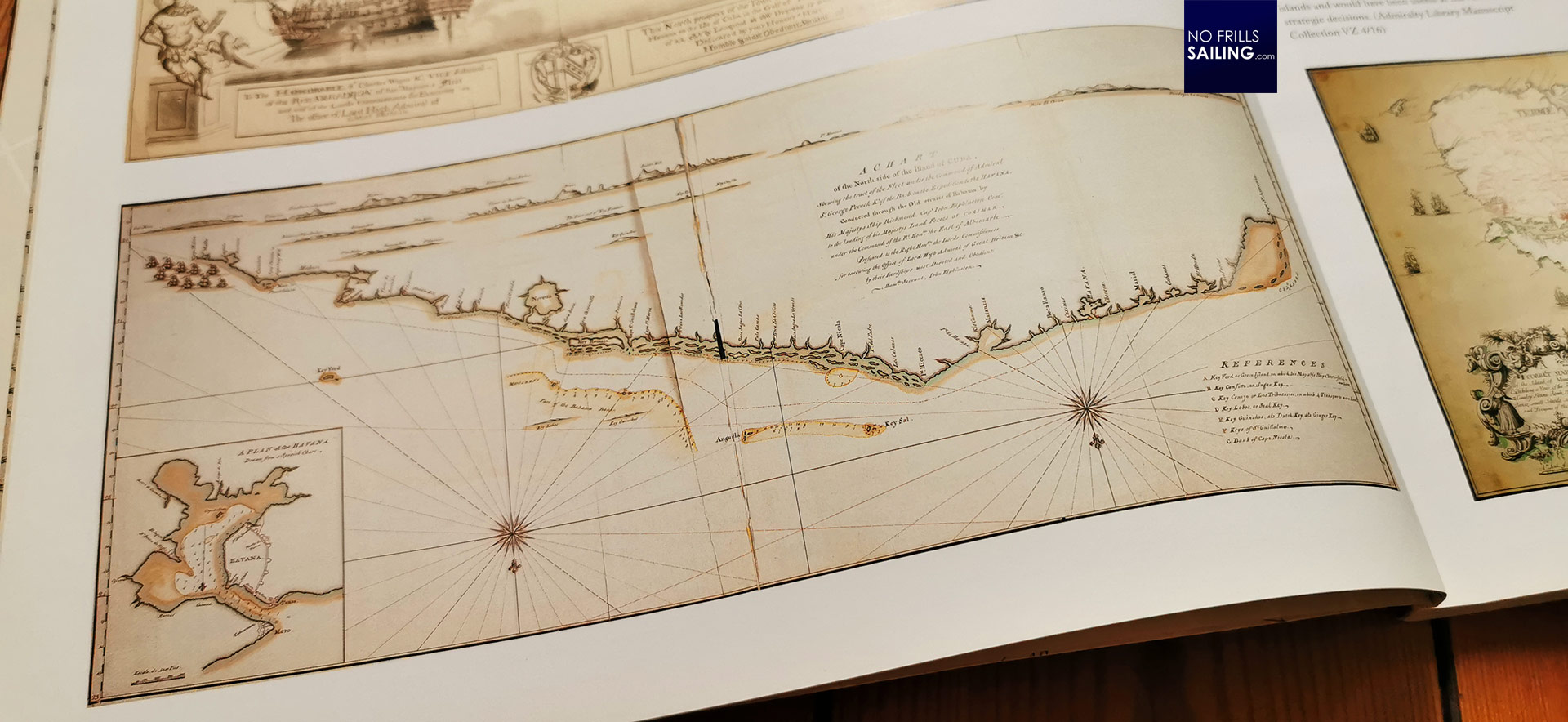

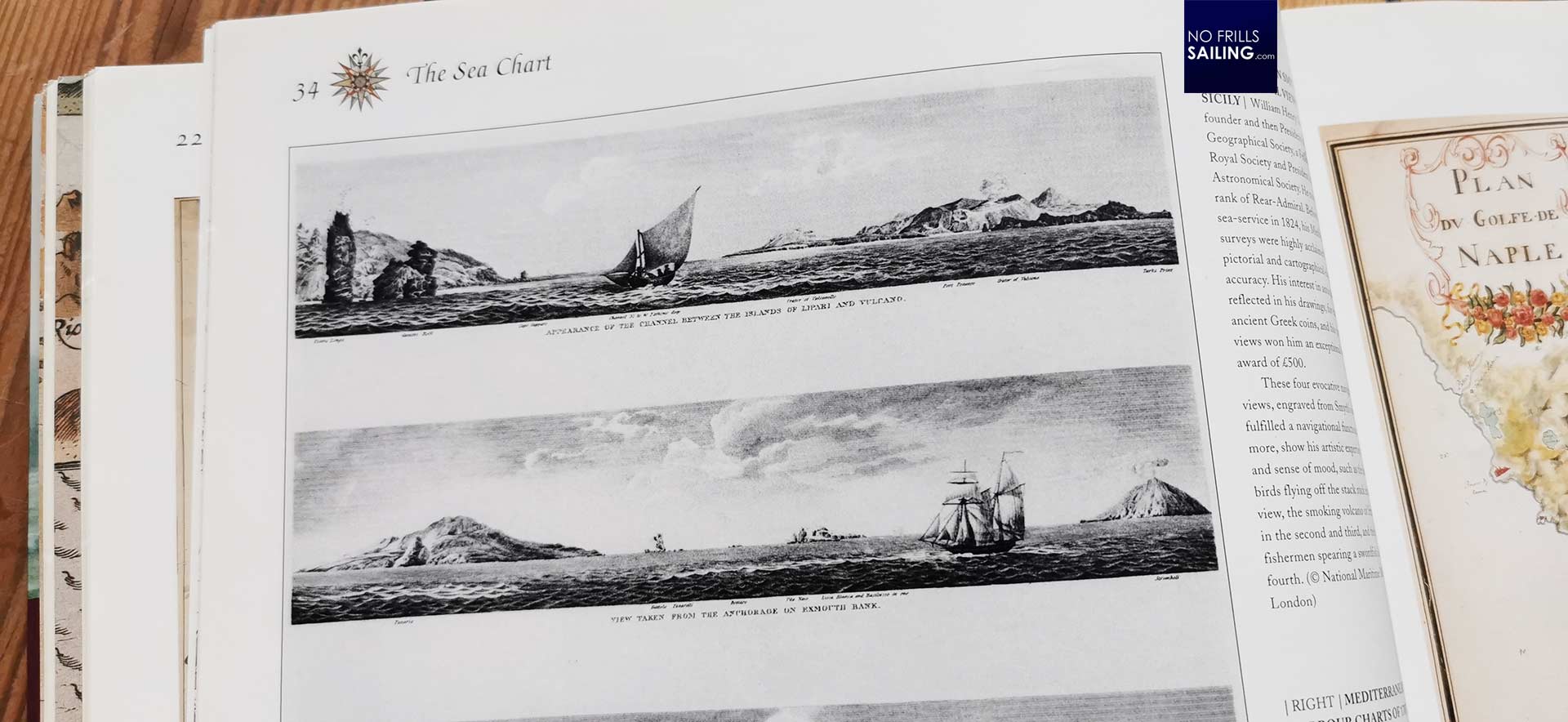

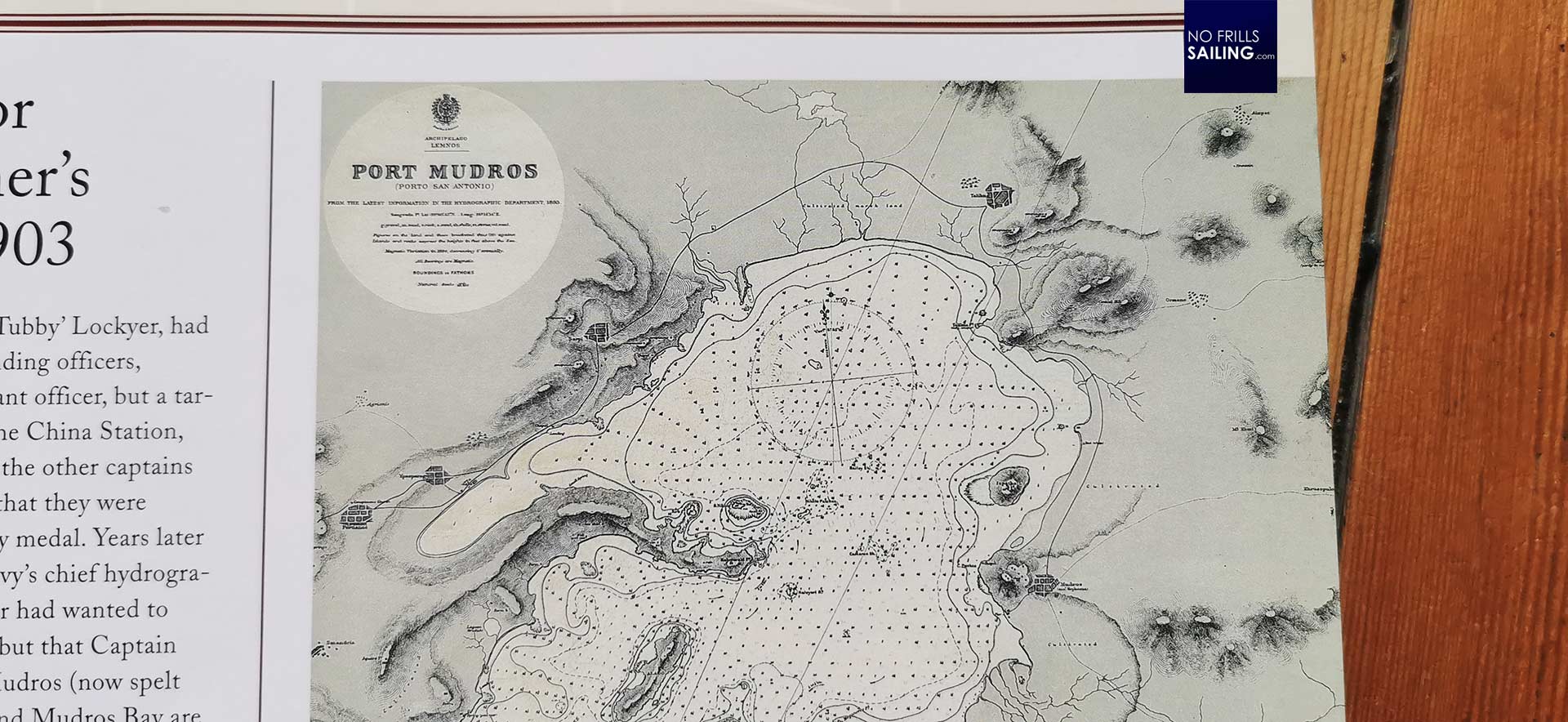

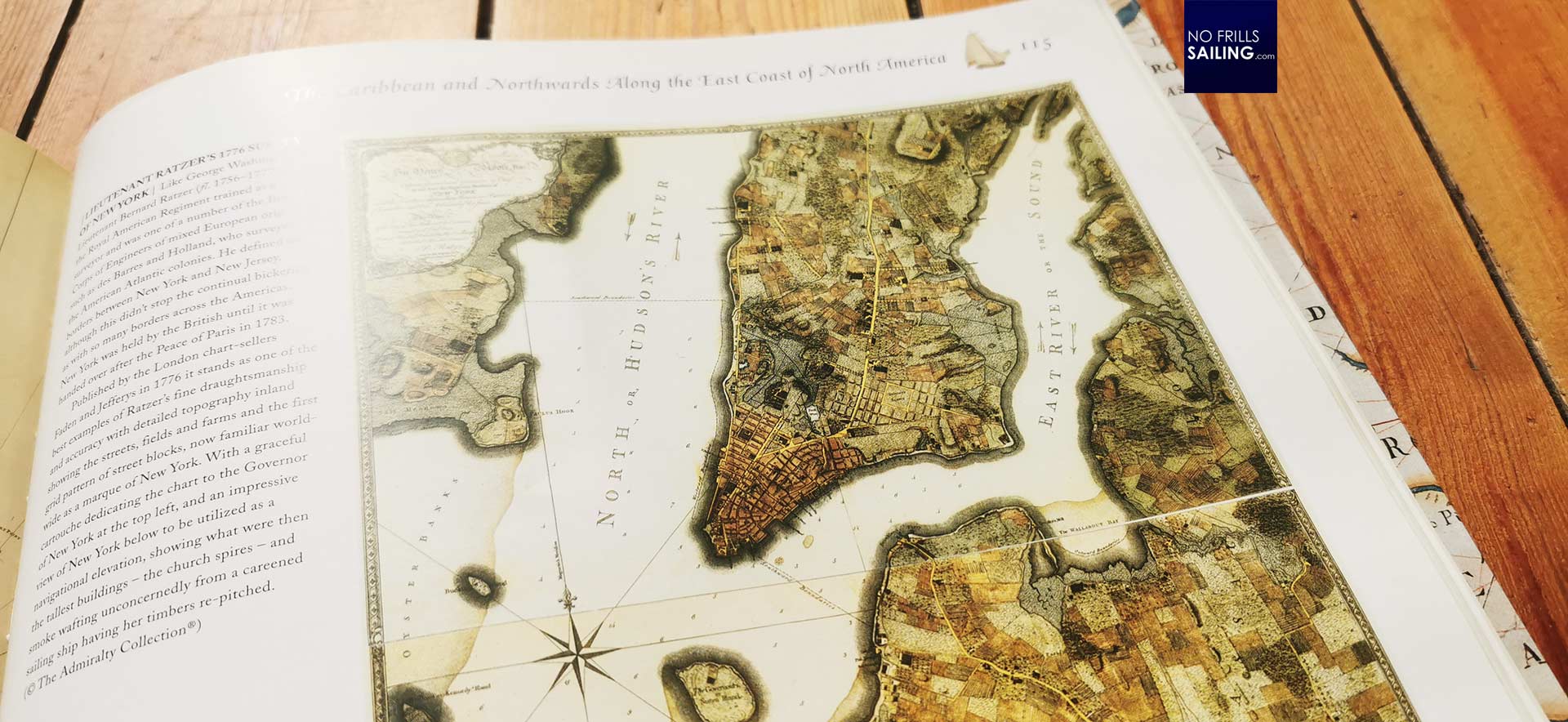

I particularly found interesting to learn that many charts of that time also consisted of actual drawings of harbor entrances and port views, completing the set of information for the Captains. In this, whole wars had been planned using these beautiful drawings to attack naval installations and capture enemy coastal towns. That seafaring was a matter of building up empires, is a fact that the book does not deny. Surely, commerce benefitted from those charts greatly, but commerce was and is always also a matter of political predominance.

Solving the problems of longitude and projection

Later the book is partitioned in chapters dedicated to cartography of the major parts of the world´s oceans. The Mediterranean, of course, being mankind´s cradle, as the most important of them, followed by the great exploration of the Americas and the extraordinary voyages from Magellan to Cook. In this, the problems of longitude and the great challenge of depicting the surface of a three dimensional sphere on a two dimensional chart is tackled, finally solved by Mercator, as we know.

Bridging to the exciting work of later geographers and cartographers, we learn how step by step the charts became much more accurate and reliable, by means of soundings taken, tidal data and topographic data, complemented by the works of the emerging science of meteorology and of course stellar navigation.

A great book for sailors

This book may not be very handy as it is very big in size, but it´s surely a great gift. This book teaches a lot which can be used practically in sailing, the least when having a landing beer when you need a good old sailing story. Joking apart: In a world where we take it for granted to receive effortlessly the most accurate satellite-data by GPS and find our way digitally by collecting waypoints on a colorful map, it is very sobering to be reminded what a tremendous effort had been utilized by generations of seamen to make our cruising life so convenient.

John Blake´s book is entertaining, full of many details and little stories. I found it very rewarding reading it and kind of re-discovered my passion for old-school navigation and paper charts. What a pity that (at least here in Germany) one of the most important publishers for printed naval charts went out of business. Maybe a catalyst for me, to try and utilize classic printed charts for navigation more. In any case, the book is great and a definitive suggestion for a purchase.

You might as well be interested in these relating articles:

Old school sailing trip planning

The unbelievable and amazing story of finding longitude

The book of imaginary islands