Last weekend, during the handover of another Oceanis 30.1 to a client, I´ve had a nice idea. As we were steaming down the river Trave from Luebeck to enter the Baltic Sea for the sea trial and shakedown, we came by a maritime legend and one of the touristic highlights of Travemuende: The tall ship PASSAT which is permanently moored alongside the river. This huge 4 masted barque is one of the very few remaining “Flying P Liners” of Laisz.

As I knew that I would have to come up for an idea to entertain my kids the coming weekend, I thought to myself of why not trying to get aboard her almost identical sister ship, the PEKING? This ship triumphantly returned to Hamburg some three years ago. It was part of the New York City maritime museum (and I remember seeing her the first time I was in NYC some 20 years ago) after the ship was almost complete rotten. New York “offered” the ship – or would have scrapped it otherwise.

A rare ticket for the guided tour of the PEKING

It´s a great luck for the maritime world and for us all who are interested in preserving the heritage of past times of seafaring, that a dedicated foundation, generous donors and not the least the City of Hamburg were so passionate and determined to bring PEKING back to her old glory that we are now happy and blessed to have this formidable ship back in her home port. And it´s much better than just that: Around 35 Million Euros and three years later, the ship can be visited by the public in guided tours.

I already came here twice but I did never had the luck to catch some of the tickets. But this time I was lucky: A party of four didn´t show up at the time so the guide took us instead – my kids were excited as you can imagine and I don´t know if I was even more excited. I love to indulge myself into maritime history and especially the “Golden Age of Sail”, of which PEKING saw only the end, and, quite tragically, didn´t had the life she should have had.

The famous Flying P-Liners

The big Hamburgian shipping company Laisz had PEKING built at equally famous Blohm & Voss shipyards in 1911 where she was launched on February 25th. She was intended to run the Salpeter business hauling up to 4.000 tons from Chile to Hamburg. As a steel-ship she had been built utilizing the latest technology available at that time. Her four masts could hoist canvas with a maximum of 4.100 square meters into the wind – impressive!

I found it intriguing to see a ship that was built completely to utilize traditional propulsion by wind power only in a time where steam engines where commonly used and the 1893 invented Diesel engine has already been in use for ships since 1903. Nevertheless, PEKING and her sister ships were so modern that in contrast to her precursors of the 18th and 19th centuries, this huge ship could be sailed by a crew as small as 31 men!

The Flying P Liners were not just cargo haulers. Her masters and owners put great efforts into designing also beautiful and fast ships. Their resemblance to the absolute Queens of the sailing ships, the Clippers, is striking: PEKING was able to sustain speeds of up to 15 knots and, as our guide told us, regularly logged tops speeds of 18 knots. This is absolutely amazing!

Seafaring made appreciable

Our guide welcomes us on the pier. We are give signal waistcoats: As a matter of fact the PEKING is officially still a construction site (and will be like this for the coming years) and as such we would have to adhere to certain rules. After she gets finished, she will be a museum and can be visited without guests having to look for their steps and have a watchout for hazards. But that makes it even more exciting, I thought – my kids agreed. The guide belongs to the foundation of PEKING ship friends and does the guided tours honorary. In his former life our particular guide was a mechanical engineer, also working for shipyards. This made his tour especially interesting as he was competent to point to the technical specialties of the boat – but he was also very fit in history, so his remarks always got a foothold in the real life of 1911.

We started on the main deck, where the freshly laid thick Teak still sprayed a great odor. He explained how a tall ship like the PEKING was sailed. Actually, it was amazing to see that on our sailing boats practically everything is still apparent, yet of course being smaller in size. The halyard winches for example – at their time a huge leap forward – could hoist the spars and get the sails up (and down) very quickly, compared to the laborious process that took dozens of men only decades before.

This winch (of which there are three aboard) could be operated by 2 or 3 guys only. They are one of the reasons why PEKING and her modern sister ships could be safely sailed with such a small crew. Our guide explained that all of the work needed to sail the ship and trim the sails had to be done on these very decks out in the open. Which may sound quite nice on a sunny lush and warm day like this, but imagining waves as high as a house, temperatures below zero and a gale off Cape Horn, where square rigged ships like PEKING could well spend weeks tacking against the wind and current to round it … it suddenly becomes not very pleasant.

The running rigging of a square rigged tallship

We proceed to the fore mast where our guide resumes explaining the wild network of lines. The running rigging. My kids and I did only listen with one ear as we tried to find out ourselves which line went where and did what. In the end, I told them, there are only two different kinds of lines needed to sail a boat: The halyard and the sheet. Of course, this is a bit more complicated on a square rigged ship.

At the tips of the spars where the heavy canvas was attached to, lines are running abaft and down. Those are used to “brace” the sparse to a 90 degree angle into the wind so that most of the energy git harvested. A square rigged ship like PEKING would sail best on a running point of sail with a 180 to 160 TWA. Maneuvers on a square rigged ship, like tacking or gybing could take between 15 and 30 minutes and demanded for a “all hands on deck” maneuver.

The crew of PEKING had an interesting work scheme. As our guide explains, out of the 31 men aboard, some Officers, the sailmaker and the ship´s cook aside, half of the crew worked exclusively on the port side and the other half on the starboard side of the ship. Out of these crews, half of them had active duty, the other half was off watch. Interesting: I always thought that a ship´s crew force would be divided by the masts, like a “fore crew”, a “main crew” and a “mizzen crew”.

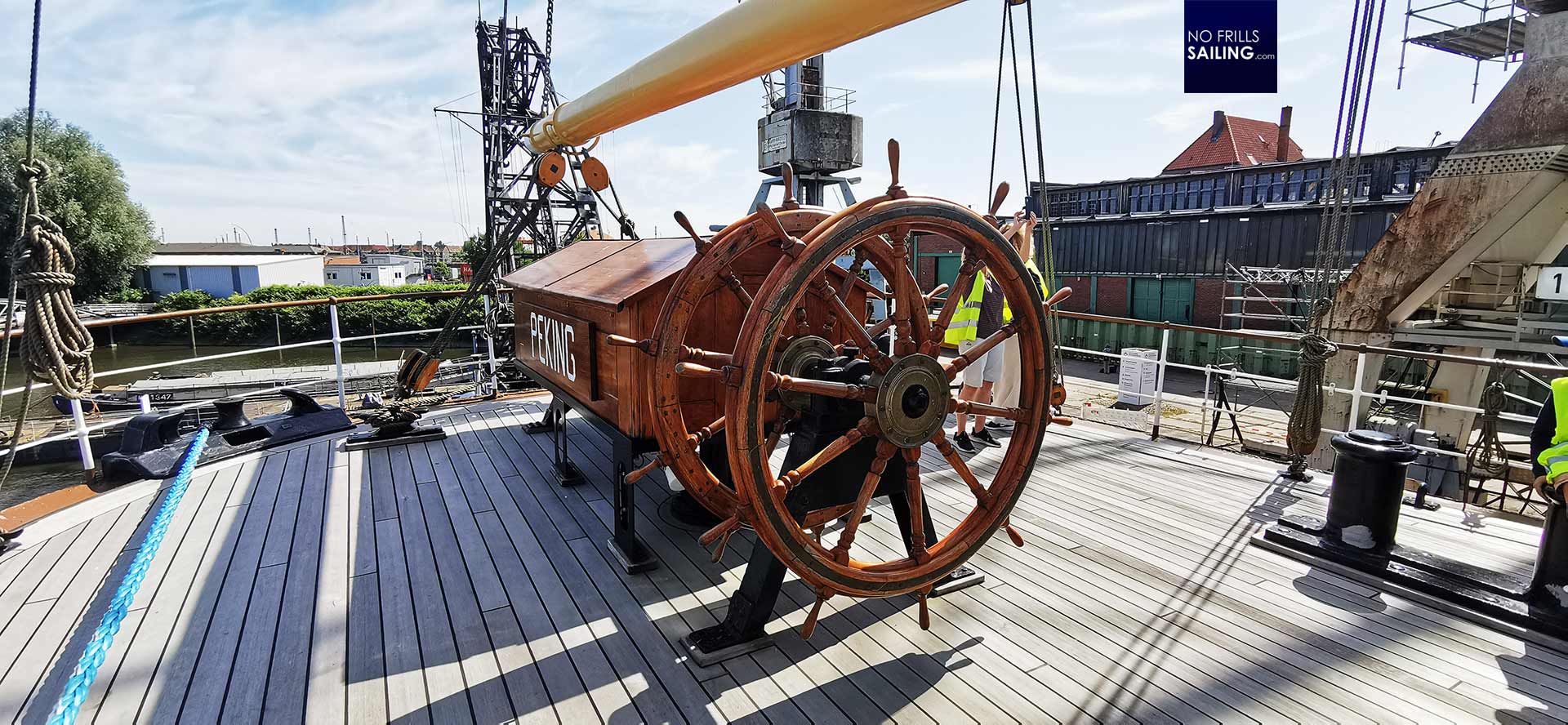

At the helm

Right on the pivotal point on deck, somewhere around the middle of the boat, the chart house and main helm station is located. The wheelhouse has already been beautifully restored – the ship´s maintenance, especially during her time in New York, was neglected. Hurricane Sandy´s flooding of New York in 2012 almost made her recovery impossible. She was a mere wreck. I rejoice and praise the work of the people putting so much effort in her restauration.

In the wheelhouse the main compass is visible as well as the main chart table. From here, the Officers would have planned the route and given orders to the helmsmen. Some of the fellow guests ask our guide why the helm was placed here and not right at the stern – like it is to be seen in all those movies. Well, at first, in the middle of the ship the movement especially in rough seas is less violent. Also, since orders had been given orally – or, let´s say, the have been yelled to the crew – it made sense to place the source in the middle so that both people in forecastle and people on the poop-deck way back could hear them.

Navigating the PEKING and steering her must have been a huge task. Imagine a ship with some 6.000 tons of displacement fully dependent on the wind. Even back in 1911, more than 100 years ago, European waters, the English Channel and alike were very busy. No radar, no VHF, no AIS. Also, no GPS, just the stars and the sun to navigate on – huge pressure! Also, the steering commands translated into the wheels went back and down to the rudder with a complicated lashing or ropes and chains. No hydraulic aid, just pure muscle work.

Living aboard a tallship

A Salpeter run to Chile from Hamburg around the Cape Horn would take months. Her maiden voyage lasted around 5 months, which was even considered fast at that time. With some 8 to 10 weeks at sea, doing hard physical labor and being available for “all hands”-maneuvers all the time, the crew needed good nutrition. For that, PEKING had two pigsties which could hold two to three pigs each as life stock.

The only “warm” and relatively dry place aboard this whole ship was the galley. So, as our guide tells us, the crew would put their at best just damp clothes around the galley where the only source of heat was working day and night to provide for food and hot drinks. There was not heating in the crew quarters and cabins – since work was a 100 per cent open air operation, the men had to cope with moisture all the time. Especially sailing in winter made this job unimaginably hard.

We proceed to the very crew deck. Works are still underway and the original compartments haven´t been finished yet. The carpenters are working on port side, having set up a skeleton marking the sizes of the cabins. To port side a bathroom, some workshops and cabins had been situated. We can go inside and have our imagination taking over.

In one of these small cabins the Officers would live alone or share a cabin, the staff Officers would be four persons in one cabin. In the back of this compartment the Captain´s cabin is already marked by a simple yellow rope: At least the size of his quarters was acceptable, I think to myself. We also get to see the port side crew quarters where some 10 to 12 men would have had their berths in one single room. As half of them were on active duty and not in the room, I thought it looked quite cozy for a party of 6.

PEKING did manage to complete on very few Salpeter runs because with the start of the Great War, World War 1, the ship along with eight other freight clippers of Laisz, was immediately detained in Chile and could not return to Germany. It wasn´t until 1919/20 that PEKING was sailed home (by a German crew) to Europe, but instead Hamburg she was brought to England and given to Italy as a reparation. But Italy had no use for such a big sailship, especially because there was no skilled crew available.

Training young seafarers aboard PEKING

Laisz bought back the ship (with some others) and re-started the Salpeter trading, under strict ally supervision. Nevertheless, PEKING had something of her “lucky time” between 1923 and 1932 as she was regularly used and also refurbished to serve as a training ship for maritime youngsters. In that, crew accommodation in the poop deck was enlarged so that PEKING could take on another complement of 43 Officer candidates for qualification and training.

In this, the emergency steering right at the stern was updated from tiller to wheel-steering so that the ship could be actively helmed from there. The youngsters learned stellar navigation from the observation deck and PEKING sailed happily. Can you imagine standing here, facing the fierce conditions of the ravaging Atlantic Ocean battling the Pacific off the Horn? American writer Irving Johnson, sailing PEKING 1928/29 around the horn, wrote his classic “The PEKING battles Cape Horn”, which, along with the breathtaking camera footage, is a most valuable piece of maritime documentation.

I stand there in awe, holding onto the steering wheel, trying to grasp the full size of this behemoth. Trying to imagine how it must have felt during the darkest of nights, howling in the rigging, a storm chasing the ship and the clock ticking for a speedy arrival. Only faint and nimble lights signaling our presence to others, a tired man in the bow looking through the dark spay, watching for flotsam or reefs. Chilling to the bones.

Salpeter: The reason for her existance

Salpeter, or Sodium-Nitrate, was a highly profitable and sought after raw material. The booming industries of Europe needed the white or transparent crystalline powder to produce fertilizer, for conserving food and of course to manufacture explosive agents. Chile at that time was the world’s largest provider of raw Salpeter – “Nitrato de Chile” – was a label for quality.

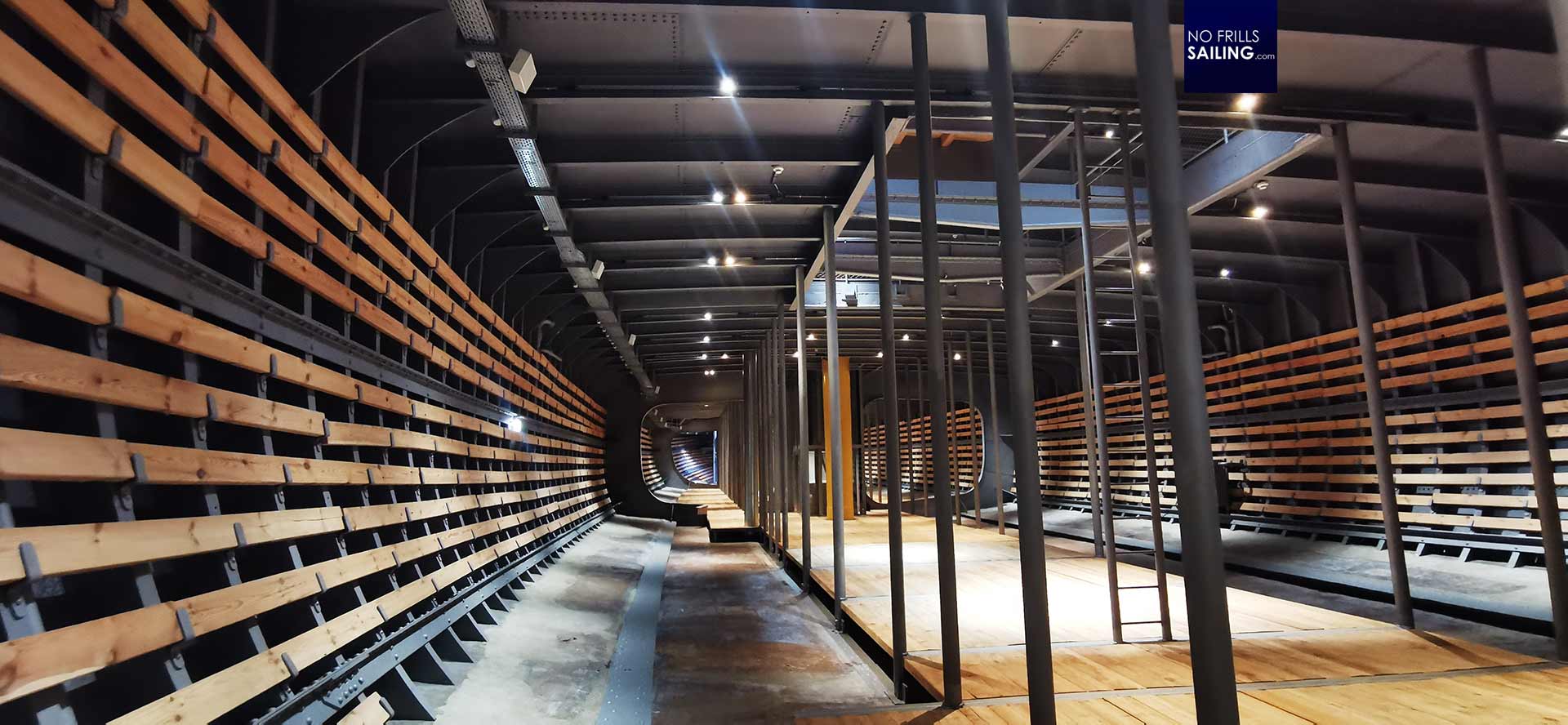

PEKING could take on 3.100 gross registered tons of Salpeter, which is a huge amount! One gross registered ton is about 2,8 cubic meters of material – and walking down into the upper cargo hold, my breath stops immediately! This is so awesome: The whole deck is just one single huge room. From the bow to the stern you can walk completely free without obstacles – the full 115 meters length of the ship. The PEKING received the Salpeter cargo in 70-80 kilogram sacks. Imagine the workload for the people loading and offloading 4.000 tons … that´s 50.000 sacks!

But that was just the start. Underneath the upper cargo deck, there is the main cargo hold. It comprises almost two thirds of the ship´s entire hull. The view from the upper cargo deck through one of the large loading holds is breathtaking, going down and standing inside this room lets your heart beat a bit faster: This is not a cargo hold, this is a Cathedral!

Our guide explains that the sacks of Salpeter had been stacked to form pyramids. That was done because a pyramid is the most stable of all three-dimensional bodies with a low gravitational point. The pyramids had been secured from moving (which could cause a ship to capsize and sink) and were never ever to touch the ship´s sides. To prevent the precious Salpeter from being subject to condensed water (that apparently was running down the ship´s walls in literal streams) the whole inside wall of the steel hull of PEKING received a wooden paneling.

The Golden Age of Sail

We roam about deep down in the ship, some 7.5 meters below the water surface. Out guide explains that PEKING, when sailing to Chile, had to take on ballast in order to insure a safe passage. This ballast was taken on in form of huge erratic boulders or rough gravel. Those, of course, had to get rid of upon arrival so the first thing the crew did was to throw out big stones in Chile.

Imagine, after 3 to 5 weeks being wet in storms, you eventually arrive to Chile and you must haul hundreds upon hundreds of tons of big boulders deep down here, bring them up via lifting blocks and throw them overboard through this small hatch. A tiring exhausting work – in the summer heat of Chile.

We proceed to the main mast where our guide points out another interesting detail of the ship´s construction. Just as it is the case in your little sailboat, a tall ship like PEKING needs to secure the free standing masts (stepped on the keel) with shrouds and stays. The shrouds also need to be connected to the ship´s hull via chainplates – only that the chain plates of the PEKING are house-sized and resemble huge bulkheads. Incredible!

The very last layer on the bottom of the hull of PEKING consisted of concrete ballast. During restauration, the workers prized open a part of this ballast to make for a free view onto the “backbone” of the ship: You can clearly see the keel and the frame of PEKING, riveted together. It´s just amazing to take this “Roentgen”-view into the structure of the ship.

A new highlight for your visit to Hamburg

Our tour lasts full two hours. Right at the start our guide said we´d be underway 60 to 90 minutes, but his explanations were so interesting, so gripping and the subject so exciting, that our group kept on asking questions and hanging on his lips when he explained yet another detail. This is what I love most about Hamburg Harbor Museum and PEKING: These are not people who are here working their jobs, these are true friend of the ship, former workers or seafarers and above all, idealists who are celebrating their passion. When we said Goodbye, he didn´t ask for money for himself, but asked to donate something so that PEKING´s restoration could go on at such a high rate and quality as we had just witnessed.

Hamburg is Germany´s most important port and one of the big touristic highlights. With the Harbor Museum (about which I had written in another article recently) and the PEKING, this city can be proud of yet another big location you must visit when you come here. Up until 2030, when the new building complex just vis-à-vis the current location will be finished, this museum hopefully will keep its charm, lovely people working voluntarily and this very special and unique atmosphere.

We wave and laugh as we leave PEKING. I am happy that she could come back, quite vividly remembering her awful and pitiful condition when I saw here in New York some 20 years ago. She is part of Hamburg´s maritime heritage and I hope that many, many more people will come and see how high seas trade was organized and how the seaman 100 years ago mastered the wild Oceans.

Closely related articles of interest:

Paying tribute to a legend: PEKING arrives from New York City

Overwhelming, chaotic, nostalgic: The Hamburg Harbour Museum

Another ship in Hamburg: The Soviet “Assassin” submarine