Last week during another class of my SSS-certification (that is the German equivalent of the Offshore Yachtmaster) I´ve had another light bulb moment I´d like to share here. Subject of the class back then was the big wide field of stability. Well, I certainly do not want to bother you dear reader with the whole set of theoretical stuff of buoyancy (although it´s really fascinating and diverting stuff) but I´d like to explain the theory of capsizing because I feel that the deep understanding for what happens there could bring us all a step closer to safer sailing and being a better skipper.

Yacht stability, centre of gravity & the centre of buoyancy

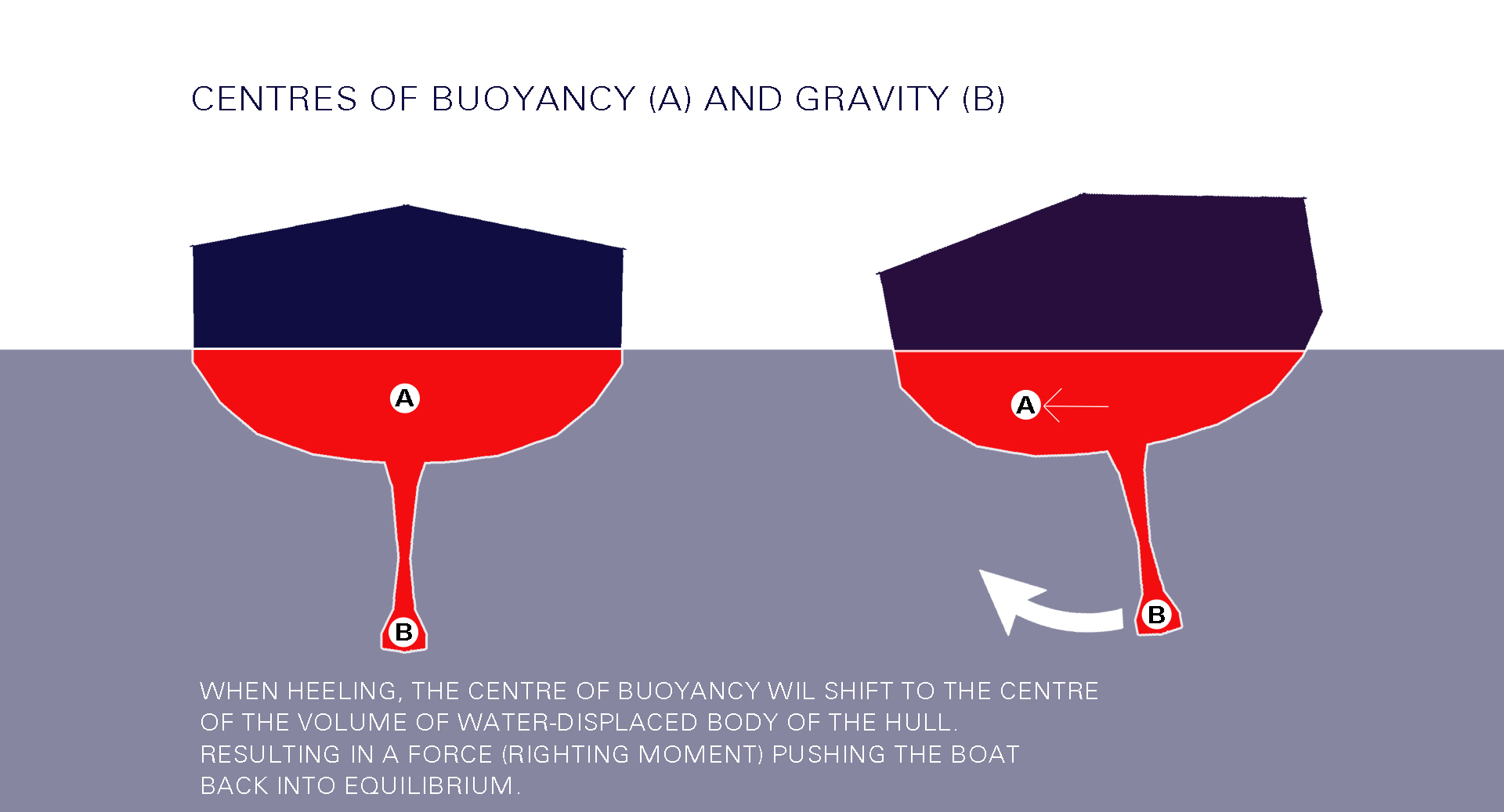

To understand the matter there are three terms we have to take a closer look onto: The centre of gravity, let´s call it point B in the scribble down below, is a point in your yacht where – as the name says it – all the masses of the boat, hull, ballast, engine, fittings, equipment and so forth – have their focus. It is worth mentioning, that the centre of gravity is a fixed point that doesn´t move. Then we´d have point A which we would call the centre of buoyancy. Here´s the first vital thing: Point A is moving with the movement of the boat since it is the centre of the water-filled volume of the boat.

Now, as you may see in the scribble above, point A has a different location within the hull depending on the position of the boat within the water. Third and last is a force, we´d call it C, the righting moment. Essentially, that is a mighty force, a lever. The farther A is from B the more is C pulling the boat back to an upright position. So far, so good. The stability-theory defines a positive stability (that´s the one we´d like to have because then the boat is floating upright) and the negative stability (no-go), that is when the boat is floating, but turned upside down. But that´s none of our business here, let´s move on and see why a yacht would eventually capsize.

Losing stability: When a yacht capsizes

Even back then when I was just eating away books on sailing and never have had sailed a single mile by myself, I knew for sure what I would prevent at any cost in foul weather whatsoever – bringing the boat alongside the waves in a storm. Short: Broaching. You must never allow your yacht to be steered this way in heavy seas! Why is that? Because this is the first thing of the recipe of catastrophe, the first act of the theatrical scene called capsize. Why? Let´s take a look on the next scribble – and maybe even without my explanation you have your own light bulb moment:

Of course, you can see it at once: If the yacht is broached, one of the next waves is approaching her (in this case) broad port side. When the wave takes on the hull it is immersed unequally in the waters of the waves: There is way more immersion of the yacht´s hull taking place on the port side. As we have learned, point A moves within the hull depending on where actually the centre of the floated volume of the hull is. So it travels to port side. Lever C kicks in and “tries” to pull back the boat to “upright”. But in this case, the “upright” is the wrong side in this situation! So, as the waves moves on and travels farther, the lever is actually promoting the capsizing, speeding it up like an unstoppable booster. It is this very scribble that brought final understanding to my brain. Because, finally the force that is normally caring for stability is in this case the doom of the yacht. Period.

Other interesting articles you might read:

What makes a yacht seaworthy?

Yardstick, IRC and ORC – what is the regatta handicap system for yachts?

Books on heavy weather sailing.