As my older son was having the fun time of his life during the Optimist sailing camp, I took my younger son for daytrips to spend the time. Although we live in northern Germany, we aren´t up so far north, I seldom visit the area around Flensburg near the Danish border. It´s a very scenic and nice region, especially if you are seeking lush nature and less people. Did you know that this was one of the heartlands for the Viking population back in the day?

Well, here´s the Schlei, Germany´s only Fjord-like inlet – this is why it is also called the “Slesvig Fjord” in the local idiom. Here´s also the picturesque town of Schleswig located, the once mighty castle populated by the House of Oldenburg: It´s descendants became kings and queens of Greece, Norway, England (yep, England) and even the Czars of Russia. Busy people … Anyway, I went here to finally meet a very special man too, not a blue-blooded buy, at least to my knowledge, but a very special one too. Jan Bruegge.

Wooden boatbuilding in the land of the Vikings

You might have read my article about a newbuild boat called Woy a few months ago. Back in the day Woy was brand new and had just been launched a few weeks prior to my visit. She is a very special boat, in many respects. First of all, she is the design of cherished Martin Menzner of Berckemeyer Yacht Design, a name you´ve come across many times over not only in my blog, but also if you´re interested in contemporary sailing and sailboat design. He is a keen sailor himself and the designer of the famous Berckemeyer aluminium yachts.

Well, as it turns out, Martin designed the Woy. It was very revealing and absolutely interesting to talk with him about the specialties and intricacies of timber as a principle boatbuilding material and how the material itself influences his design. You should definitely check out this interview as well! That said, the man who initiated the whole project, the idealistic and forward-looking entity behind Woy is Jan Bruegge. His shipyard and workshop is located in a small (and I mean very small) village called Koenigstein at the Schlei. The view out of his bureau goes over a juicy grass meadow with a herd of happy cows directly onto the waters of the Schlei.

Jan Bruegge uphelds the traditions of handcrafted boatbuilding. Moreover, his aim with WOY is to bring back a renaissance of this age old boatbuilding material: Timber. WOY means simply “WOoden Yachts”. But it sounds like a cry of wonder, a neologism of “wonder” and “joy”, of “wood” and “wow” … you name it. This young man has a mission: Bringing back wooden boats in a serious way. Not a makeshift garage built. Not as a cheap alternative. For Jan, wood is a wonderful, modern, strong and absolutely capable material to make beautiful boats from. His Woy is not the start, he already demonstrated with the well-received ELIDA that wooden boatbuilding is indeed a thing of the future.

Here, at this location, not far from one of the most important and biggest Viking cities and trade junctions, Haithabu, Jan started his venture. A quest for the perfect wooden boat, a search for likeminded people to join on his journey, both as employees and customers, his WOY, a 26-foot performance daysailer, just entered series production. I arrived, welcomed warmly by an all-out smiling master boatbuilder, to see, how the WOY is made – this is what I´ve witnessed …

The ball that got it rolling

As we´ve entered the workshop, the very boat, the one that started the whole thing, stood right there. The Woy. She throned graciously on her trailer. High up in the air, just underneath the ceiling. Like an insect of some sort, an alien big – compared to your ordinary sailboat, the Woy looks otherwordly. She indeed is something very special.

You can read my article about my first encounter and sailing experience with Woy here, packed with more and detailed information about this boat. Her deep draft when the drop keel is down is 1.90 meters. This makes for a nice contrast – as the hull is very narrow and sharp, she indeed bears more resemblance to an UFO of some kind.

This knowledge, and the fact that Woy is made from wood, makes it even more special. You wouldn´t expect such modern lines, so much design and beauty, from a wooden boat. Up to know, when talking about boats made from this natural material, at least in my head, only pictures of those bulky DIY-builds like Mini 6.50 or Globe 5.80 appeared. Even the wood-made RM Yachts, after all designed by Marc Lombard and build by a shipyard with over 35 years of experience in building epoxy-infused wooden yachts, cannot compete with the refined and beautiful design.

The almost organic shape is alluring, looking from any angle at the boat is a satisfying. Like astounded contemplators speechlessly discovering Michelangelo´s David for the first time, even my son´s eyes started to sparkle. Usually, such a reaction is limited to the big-time impressive super(expensive) yachts. Woy is different, in every aspect.

Serious about series production

The reason for my visit to Jan´s workshop is that twofold. First, of course, I was interested in how such a boat is made. What is wooden boatbuilding about? How it´s made? And secondly, from an entrepreneurial standpoint, I wanted to talk to him about his vision of bringing back wood and timber as principle boatbuilding material and commercial implications. Is the Woy just a nice boat to look at? A mere news headline and serving as a fig leaf for an industry that cannot really change?

Well, one thing is for sure when it comes to the Woy 26: Series production is not a marketing headline, it´s reality. One of the first things I notice in Jan´s workshop are the racks and big moulds dedicated to churn out more Woy sisterships. As a businessman, you wouldn´t invest in these tools – absolutely necessary to guarantee a steady high quality from unit to unit – if you wouldn´t want to make more. So, no, the Woy 26 indeed is not a marketing gag!

Next to the hull rack, an elaborate mould is set up. Another Woy 26 is in the making, the fine raw hull can be seen. There´s even a second mould which Jan showed me (asking me not to show it for reasons). This means, that Jan had invested a lot of money, effort and precious space in the workshop to set up series production. While the first Woy remains property of the company and serves as show boat and testing platform, Jan proudly confirms that up to this day two more Woys are had already been sold. That´s great news already! And best about it is, clients are international, meaning that Woy´s message has been acknowledged way farther out that just here in the region and Germany.

100% handcrafted wooden boatbuilding

Backed by this first, very promising, commercial success, the workshop is brimming with people. Jan´s company employs 15 people, from master boatbuilders to apprentices. Also, a good sign: All of them are smiling and nodding friendly upon seeing me roaming the premises. Motivated people – a premise for good quality work. I witness one of them kneeling before the hull, so let´s take a look at how the Woy is made in detail.

“Wooden boat”, what does it mean? Well, usually, to safe time and money and also for not having to invest in making a costly mould, wooden boats are build utilizing the so-called “cold moulding”. Therefore, thin straps of veneer-like wooden sheets are laminated over one another to form the hull. To achieve the shape of the hull as desired, these are applied over a set of construction-frames, forming a “male” model that is turned upside down. This process saves time and money, but also space: After the hull is made, the rack, or cold mould, can be disassembled and stowed away.

In the case of the Woy, Jan decided to refrain from classic cold moulding over a rack, but asked renown Knierim works to make a proper full mould. That´s basically a full male counterpart, like a plug, of the female hull. Woy boats are indeed made by layers of wooden sheets, but with a distinct difference: Instead of hand-laminating and glueing the individual sheets, they utilize vacuum infusion. Therefore, to achieve a proper, seamless and perfect smooth hull, the full mould is necessary.

The outcome? A perfectly broad and evenly saturated hull. With vacuum infusion, the resin will reach any corner and every pore of the material. As the power of the vacuum makes for the distribution of the resin, no human-made divergencies in the amount of resin will occur. In the end, a much thinner, hence more lightweight, and much stiffer hull is the result. Four layers of wooden sheets make a hull, as I could clearly see. The whole boat will weight not more than 1.120 kilograms …

Something very extraordinary

I am astonished about this one detail I often acknowledge when looking at boats, no matter which kind: The effect of seeing it in the water and outside. Usually, yachts appear to be much bigger when seen outside, which is of course logical as we only see the upper parts when they float. Adding the usually hidden submerged part of the hull, adds to the impression. Also, perspective plays a role: When in the water, we usually have the high ground, looking down.

Now, with Woy, it´s the same effect: She is a damn big boat! About eight meters in length, that´s approximately the size of my GEKKO. Maybe the fact that the body of hull #2 was also turned upside down, added to this optical illusion. She is indeed a proper sailboat, a fun machine. And something very special. The hull I could see that day had already been infused. A single layer of glassfiber covered most of the wetted surface already, what was still missing was the stem. This is made separately (but it wasn´t manufactured as of now so I cannot show it) and attached to the now flat forward area.

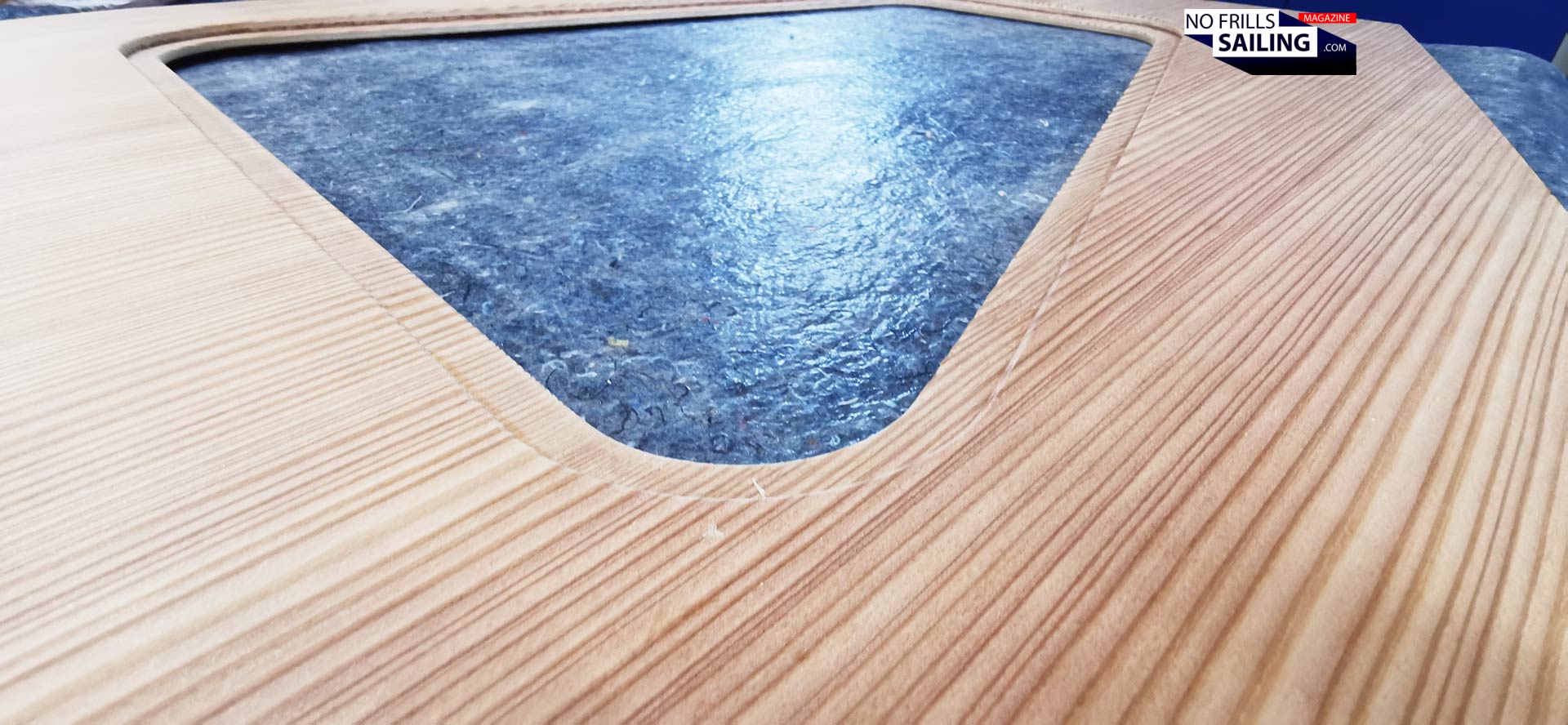

Right next to the boat on the Knierim made mould the raw wooden sheets utilized for making the hull were piled up. Pinewood of best quality. Cut to approximately 1.5 to 2 mm thick (or better: thin) sheets, this is the material of which the outer shell of the Woy is made. Oh, and by the way, cold moulding is not reserved for wooden boatbuilding exclusively: Many aluminium yachts are built that way too, as you can see when browsing to my article about the Alubat shipyard. But let´s stick a bit with the material …

Wood as a wonderful material for boatbuilding

You know what struck me, latest when I held the wonderfully grained sheets of Pine in my hands? The smell! I suddenly realized that Jan´s shipyard didn´t had this distinct and very specific smell that is so common with boat production facilities: The sharp stench of styrene and other chemical components utilized in classic GRP boatbuilding are usually more or less apparent when visiting a shipyard. Not here.

The workshop smelled like … a fresh Teak deck or a classic joinery. Of course, by the way, tropical timber is not used here … so, it may be smelling like Teak, but there is none. But this workshop indeed is a joinery more than a shipyard in the sense we think of it: Even if they work with Epoxy, glue and vacuum infusion here, there´s no need at all for breathing masks, at least for protection against hazardous chemical vapors. Wooden dust from sanding is the only occasion to wear a protective mask here, thankfully, this dust doesn´t come with an aggressive

Jan´s vision of triggering a kind of renaissance of wooden boatbuilding has many reasons. And I lengthy spoke about this with designer Martin Menzer already. One big reason is the colossal waste of precious crude oil-based products and materials, of energy and single-use plastics in GRP-boatbuilding. Although many undertakings are on the way to change that, jan´s approach is a different one: Why not utilize the one really sustainable material? The one that is really growing back? Timber, like Oak or Pine, have been utilized to make ships for centuries – proven material!

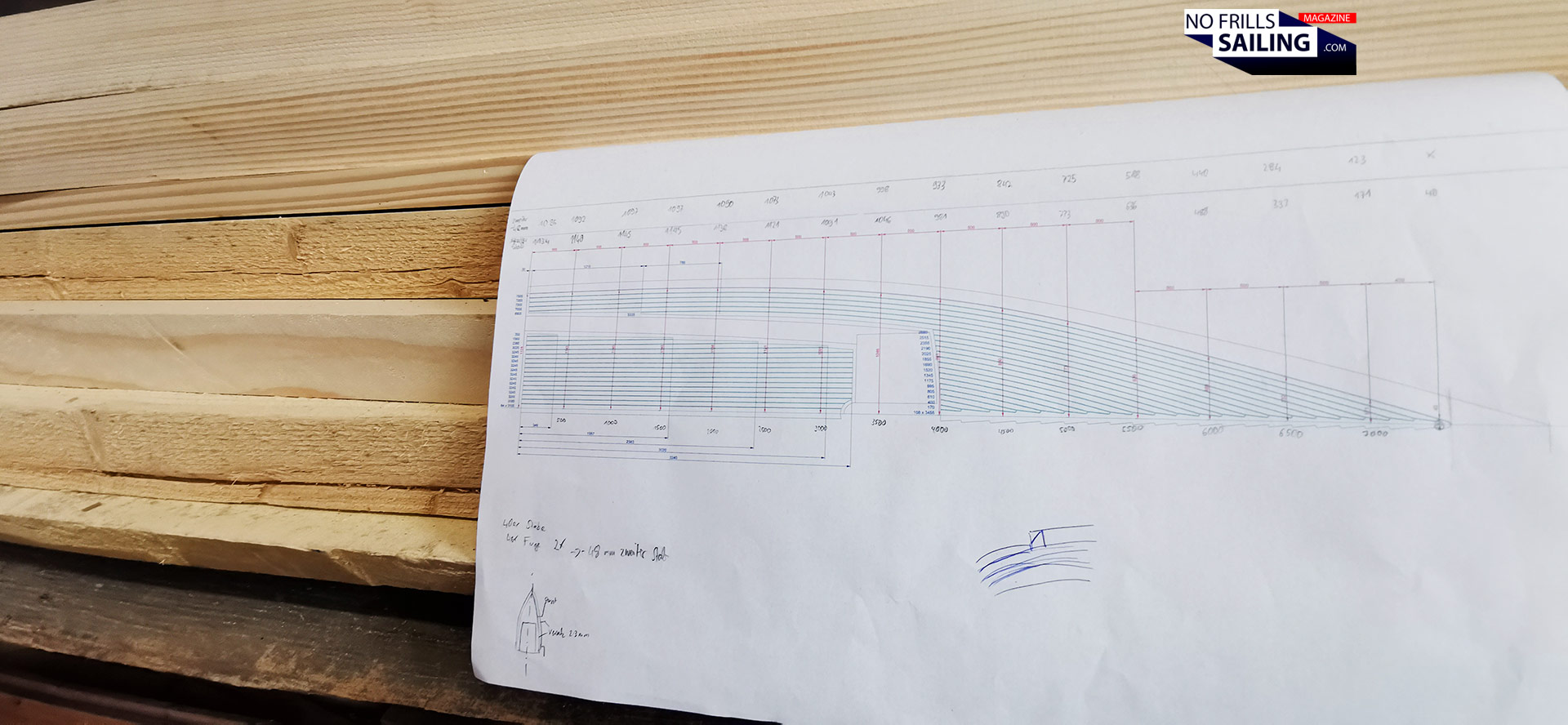

Combined with modern production methods and – yes – also with modern materials like resins and glassfiber, production techniques like vacuum infusion, it must be possible to bring back this wonderful material to boatbuilding, even in a larger scale. He shows me a rack where the raw deck battens are stored to be put on the later boats: With his fascinated, glistening eyes he points to the perfect quality of the battens. “See the tight grain structure? That´s just a perfect batch and it will look marvelous when on the boat.” Above the package, a working note of the layup-plan for the deck of the Woy is pinned to the wall: Here they are again, the modern world CAD plans, computer aided, exact to the fraction of a millimeter.

Antique, but not antiquated

No, wooden boat does not necessarily mean clumsy or crude. I´ve visited many people who are on the same road as Jan. Mostly one man shows, following their dreams. DIY boats like the Didley Dux Mini or Globe 5.80-kits. Fascinating and cool, yes, but often lacking the intricate style, the fine lines and most of all, the lightweight building approach. In this, most of these boats are hard-chined, more robust and heavy constructions (which is perfectly fine given their intended use). Woy however shows a different side.

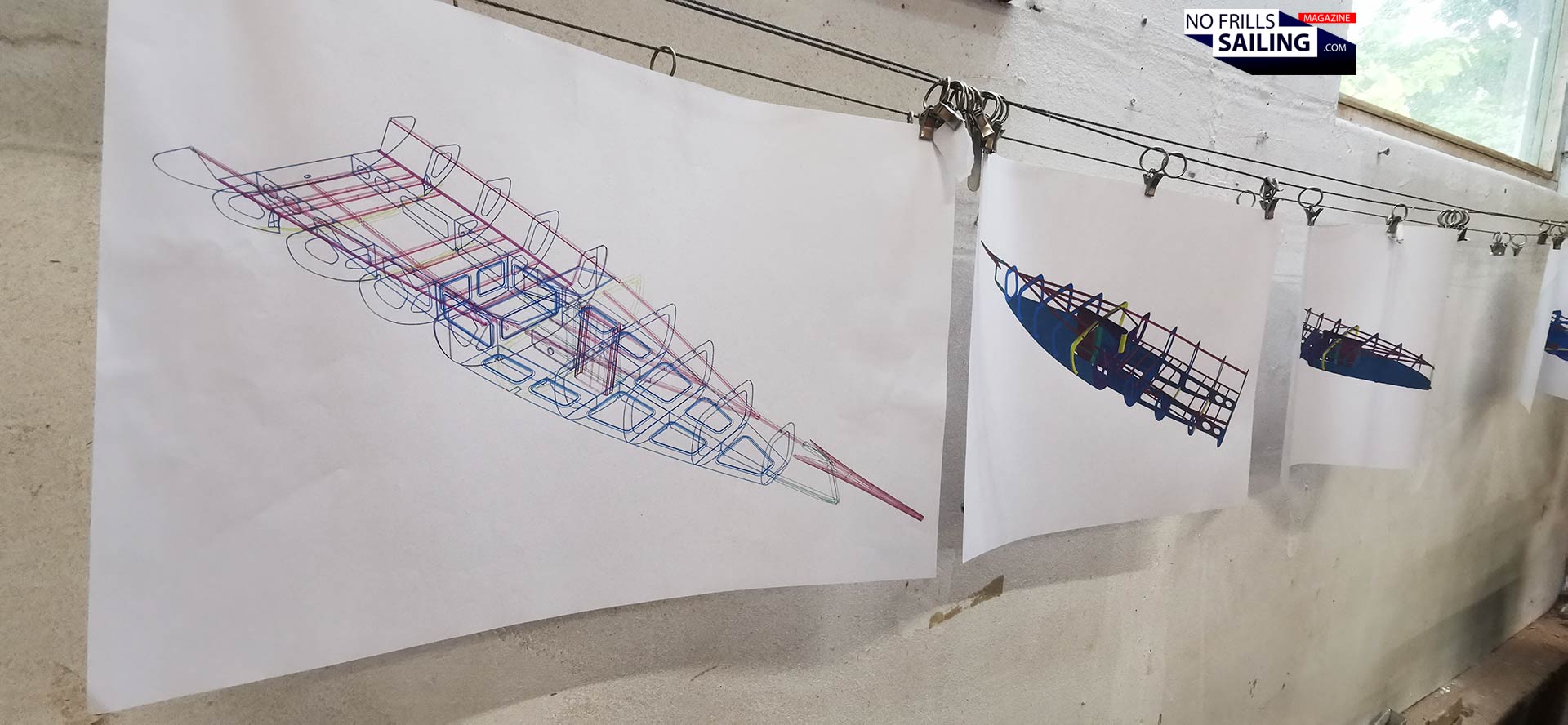

Another set of construction plans are pinned to the wall. These are elaborate 3D-printouts. Clearly CAD-generated, showing the inner workings of the Woy. The structural composition of the boat´s bulkheads and framework much more resembles a state-of-the-art IMOCA racing yacht than the thick DIY-plywood boats. The Woy by no means is antiquated, her basic construction can easily take on any “modern” concept – as Martin Menzner told me, only the very individual properties of the used material have to be taken into account when designing a wooden boat. The design process itself is always the same.

The fascination lies in the combination of traditional materials and also manufacturing processes with the seemingly boundless possibilities of nowaday´s technology when it comes to the boat design. If you tread wood as a “normal” material that is just replacing glassfiber mats and resin, everything is possible indeed. Proof of this is Woy, but also the newbuild wooden IMOCA 60 racing yacht of French sailing legend Marc Thiercelin, currently under construction to take part in Vendée Globe of 2028.

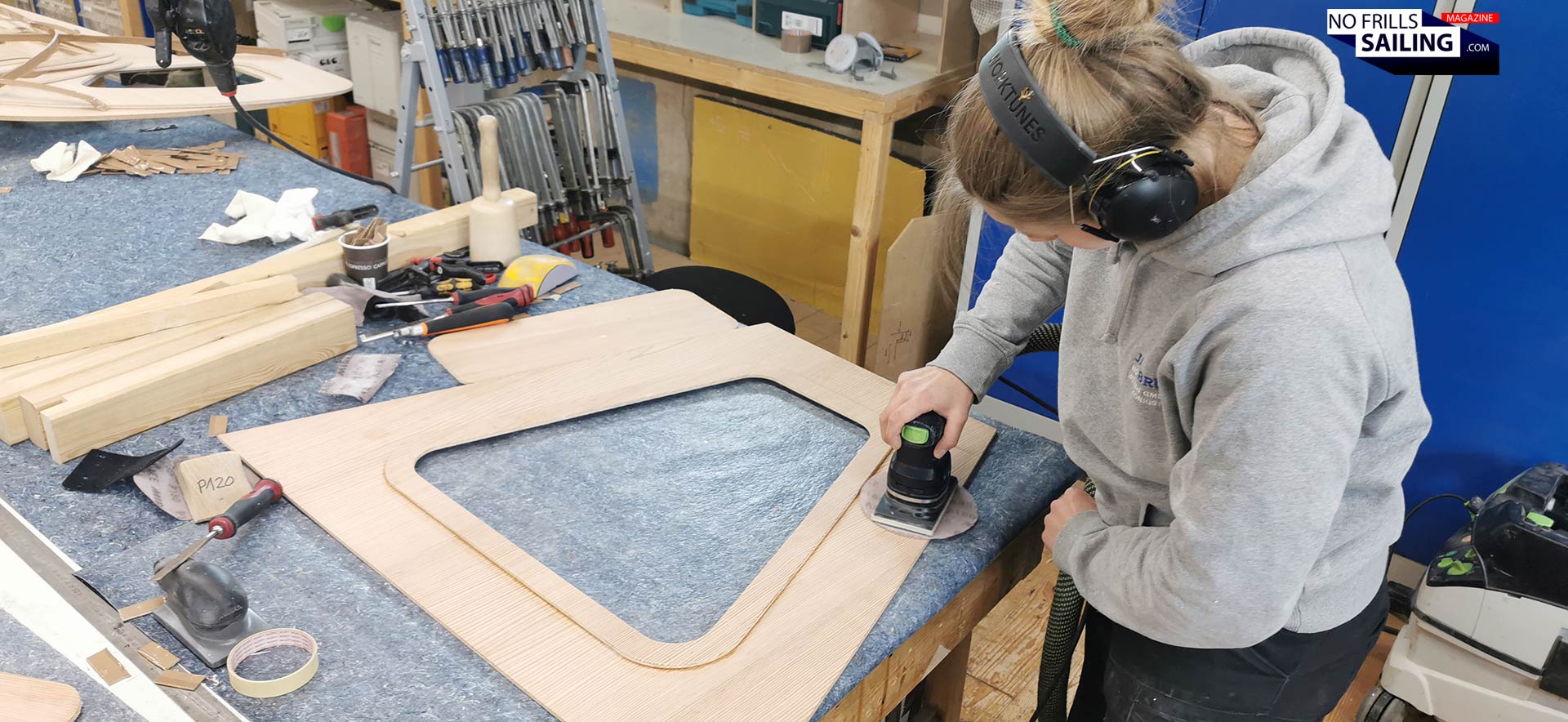

Combining our present day with this century old boatbuilding material also means that century old handcraft techniques and tools need to be utilized. As one of Jan´s staff tells me: “At last I can work as a proper boatbuilder!” That means, instead of rubber gloves and polyester-spilling rollers, the guys here work with different sanders, put also planes and chisels. Tools, usually not seen anymore in classic GRP manufatories.

At another workstation I can witness how parts for the Woy are made. The frames and bulkheads of the structural construction of the boat are predominantly made from Oak or Pinewood, some massive, some high-tensile plywood. These are pre-cut by CNC machine and finished by hand, or entirely made individually by hand. One of the guys is sanding a part, frequently taking off the machine to check the outcome, re-engaging only to check after a few strokes again. Experience, a sense of proportion and visual judgement: There´s more than enough room for a craftsman´s expertise in making these boats.

It´s this combination, I guess, which makes it so interesting to working here. Usually, “old school” wooden boatbuilding is restoring old yachts, real ship´s carpenter´s work on classic schooners or pilot sloops. Fascinating as well and its own world – as for Woy and Jan´s shipyard, I love this unique combination of this 21st century high-performance daysailer with full carbon rigging and traditional handcraft techniques. I guess, his employees fancy that as well.

Modernity is not vilified

Of course modernity is not something bad! This is very important for Jan: He and his fellow employees are not that kind of guys who condemn modern techniques and materials. By far not! This may also be a difference to many wooden boat projects. It´s not a wind-powered dreamland of an all-vegan happy place. It´s more trying to get the best out of both ends of the spectrum: Best shown in the tools apparent in the shipyard.

On the one hand, you have all these traditional tools any ship´s carpenter and joiner would be using since hundreds of years. Mostly manual work, real handcraft powered by experience, dedication and passion. Literally hundreds of screw clamps and dozens of gauge models in all shapes imaginable for rounded edges, skylights and such are a testament for this. These, however, are counter-balanced by state-of-the art tools, like high precision bandsaws, CNC milling or vacuum infusion.

As I mentioned, Woy doesn´t ban the use of modern materials and production techniques out of some sort of political activism. The use of carbon fiber, for example. It´s a great material and it certainly has its raison d´etre in boatbuilding. The rudder blade of the Woy and also the tiller are made of this high-tech material, as Jan explains showing one half of the mould. Apparently, the craftsmen at this place also know how to utilize these fibers.

The carbon tiller is a work of art. He shows me the freshly made steering for one of the new Woys. It´s always fascinating how beautifully this material can be arranged, how extremely lightweight and incredibly strong it becomes. It´s this exciting combination of boatbuilding tradition and traditional materials with high-tech nuances and accents which makes the Woy 26 so special. But it goes beyond this as well.

As any boat, the Woy has a drainage for ingress water. The little inconspicuous outlet is located at the transom right above the waterline in the boat. Jan shows the little oval. Normally that´s a detail you wouldn´t dare to waste any thought for, much less money and time. But not here: In his hand, Jan has a plastic part that looks like a simplified model of the human heart´s aortas. It´s a custom connector that bundles three supply pipes feeding the water outlet of the Woy 26.

Jan explains, that this part is 3D-printed and had ben custom developed and constructed for his Woy. He puts it on a table and disappears in the storage area next to the workshop. After a minute or so, he returns, his hands full of plastic packages. Pouring the products on the table next to the 3D-piece, I understand what he wants to show me: Instead of utilizing these clumsy standard parts, it was worth the time and effort to design and print this custom-made.

Jan smiles: „It looks way better, safes space on the inside and by the way, weighs 400 grams less.” No, it is by no means a dogmatic, modernity-denying venture here at Woy. On the contrary: These guys are really embracing technology and advancements, trying to use it at its best where it really makes sense. 3D print, I understand, is one of the big topics and major trends potentially more and more changing the way boats are built – and ultimately, how they are designed in the first place.

Can this be the future?

That´s the big question, right? Can we imagine a future where everyone can still acquire a boat for pleasure, but without using up too much precious crude-oil based and energy-intensive raw materials? Could it be possible to introduce sustainable and renewable materials in a large scale, reducing waste? And ultimately, is – even partially – a circular economy possible by recycling and re-using materials? Efforts on so many fronts are underway. Both by the big players as well as by enthusiasts and smaller companies, like Jan´s. Apart from getting to see how these beautiful Woys are made and by whom, the best part of this whole visit to Jan was to see my son. The excitement for the things going on in this showroom, his unfiltered and spontaneous reactions to what he saw, are just priceless. This young fella doesn´t know anything about GRP, the intricacies of boatbuilding, the waste, the energy, the details – all he has is this “built-in” fascination and passion only a child can have, unspoiled, unbiased.

The way my boy was drawn towards this boat and watched the craftsmen doing their work means so much to me. At least, it´s a clear sign or indication that the things happening here at Jan Bruegge´s little shipyard are something very, very special and precious. In this I can only hope that more people decide to invest in a boat made like the Woy. And eventually, order bigger units which will ultimately show that sustainable boatbuilding and full-fledged cruising is not an empty marketing shell, but can turn into reality. Into a very beautiful reality.

Related articles of the same topic, check those out too:

All articles related to wooden boatbuilding – hashtag #woodenfuture

Making a Mini out of plywood – Mini 6.50 and Globe 5.80

A wooden IMOCA for the Vendée Globe? It´s in the making!