Last week my colleague and I found ourselves meeting up at a marina´s outside winter storage for a field meeting with the owner of a Beneteau Oceanis 41.1. This man is a well-known client of our company now willing to upgrade from 40 feet to 50 feet which brings us in the position of taking his old boat as a trade-in. Now, that´s common practice: We know each other for more than 2 years now and this 41.1 is certainly a great boat – one of the first 41.1´s I was ever sailing on myself. Nevertheless, I´ve brought my dear mate with me who not just happens to be in charge of our company´s technical department but is also an officially certified expert assessor for boats.

For both the owner as well as for our company assessing a trade in boat is a must: On the one hand we do not want to “pay” more than the boat is actually worth, want to minimize the risk of buying a boat with damage or high refit-costs due to disproportionally high wear and tear and on the other hand our client can expect an objective, neutral and official assessment of his boat to evaluate the real value of the yacht. I of course attended this 3-hour freezingly cold appointment for sheer curiosity as I have never been part of such a venture before.

Of course, on that very day, my colleague wasn´t there as an employer of my company but in his function as a neutral assessor – and this is what I encourage him to pull off in front of the client as well. Don´t hide anything, don´t make anything look better than it is but also do not intentionally bash anything to decrease the value of the boat. I am sure that this is something we owe to our client who is investing not just in a new boat but also re-newing his relationship to our company, putting another round of trust and goodwill into it. For me, as well, a neutral, honest assessment increases the chances for a later sale of this secondhand boat to a new owner. Now, let´s see how my colleage went through his check list: And maybe you can learn for your next used boat shopping trip how to do it on your own as well.

The used-boat checkup: Hull and appendages

First of all let´s have it clear: This was just the first of two appointments we need to evaluate the value of the boat. Taking a look at the boat when it is outside the water is one step – seeing in fully stepped and rigged in the water is a second appointment. Evaluating the boat outside is a must: That is the only way to be able to take a look at the submerged part of the boat and some of the most crucial parts of it: Keel, rudder(s), shaft or saildrive and the bow thruster of course.

„Most used boats are in the water when a possible client asks for a visit and so they are not able to check the keel”, my colleague says whilst kneeling down checking the front of the Oceanis´ keel: The abrasion of antifouling at this part is a safe sign of a grounding. The antifouling has been sanded away, making visible the sub-layers (different color) and even the primer. As no cracks or defects on the cast iron of the keel are visible, the conclusion is that this keel has been in contact with muddy or sandy ground and not stones. That is indeed luck for the boat and – as of now – must not mean bad for now. My colleague then gets up and checks the joint between keel fin and hull.

“Most groundings occur in forward motion of the boat. In this, the keel stops the boat abruptly and due to inertia the hull exerts lots of force. This can result in a compression right in front of the keel fin and ripping at the rear end of it.” So, he checks thoroughly if he could find cracks in the GRP of the hull, ripples or splinters. On our Oceanis, luckily, there is none of it all: Our owner recounts this incident when he slid through the muddy ground of his home marina. No shock, no hit, just smooth sliding through mud. By looking at the downmost tip of the single rudder – all antifouling protection is gone as well, my colleage can corroborate this story: “The rudder is far more sensitive to pivotal forces exerted by groundings – if something bad would have happened, this rudder would bear far more damage, abrasion and possibly cracking at its tip.” He jerks the rudder blade in every direction including up and down: No play. Everything is fine here.

Looking at the keel, we check for rust. Most production boat keels are solely made from cast iron. Not steel, most do not even have the very expensive lead: “The keel fins are protected by thick layers of filler to make them smooth and streamlined and a special protective paint when the boat is assembled in the yard”, says my colleage. But over time aggressive salt water, the ablative effects of the water streaming around the hull and chemical degradation of the protective paints and antifouling will make the keel rust. That is nothing to worry about too much if the rust isn´t completely eating away the keel. In our case, it´s just a very small area that will be taken care of when the boat will receive it´s antifouling refreshing in the coming weeks.

We check the anodes, which are all new on this very yacht and also take a look at the bow thruster. Will the props move freely without resistance? Are the showing damage, possibly from objects like wooden sticks or rope or any other floating waste entering the thruster tunnel? In our case all is fine and the props just look like brand new: I cannot believe we are looking at a boat built in 2018! Going around the hull, my colleague looks meticulously for cracks, dents or scratches in the hull. First on the submerged part, especially around the waterline with focus on the front. Then above waterline: “Most slices or hits occur when landing or maneuvering the boat, like hitting a pontoon or a bollard.”, he says and notes every scratch on his check list. I welcome his statement that outside check is done and we proceed to the yacht´s internals.

Engine, water system and electric circuits: Most expensive parts

On a used sailboat, the most expensive parts which mostly show the biggest wear and tear are the Diesel engine and the water circuit. In our case, we activate starter battery and light up the engine (without starting it of course, that´s something for the second appointment in spring) to see how many engine hours the Yanmar Diesel has acquired. That´s a surprisingly little amount of 313 hours so for – for a boat this big and 3 years in use, 100 hours per year is not a lot.

We open all access hatches to the engine compartment and our surprise grows even bigger. The engine bilge, the engine itself, all pipes and parts look as if the boat has just been delivered a month ago: No oil, no dust, no dirt. My colleague is excited: This is definitely something a new owner will appreciate very much in his new boat. A well-kept, clean engine with virtually no runtime is a definite reason for buying. You do not want to pay for an engine replacement in a boat like this!

My mate had checked the saildrive from below the boat prior to this and had found no signs of damage or lack of maintenance as well. The owner presents us with the ship´s book which is part of the yard´s product and can prove a consistent maintenance done by certified and professional Yanmar-technicians. You should definitely ask for such a record too. Mofing to the port side aft cabin we remove the panels from the berth and check the batteries.

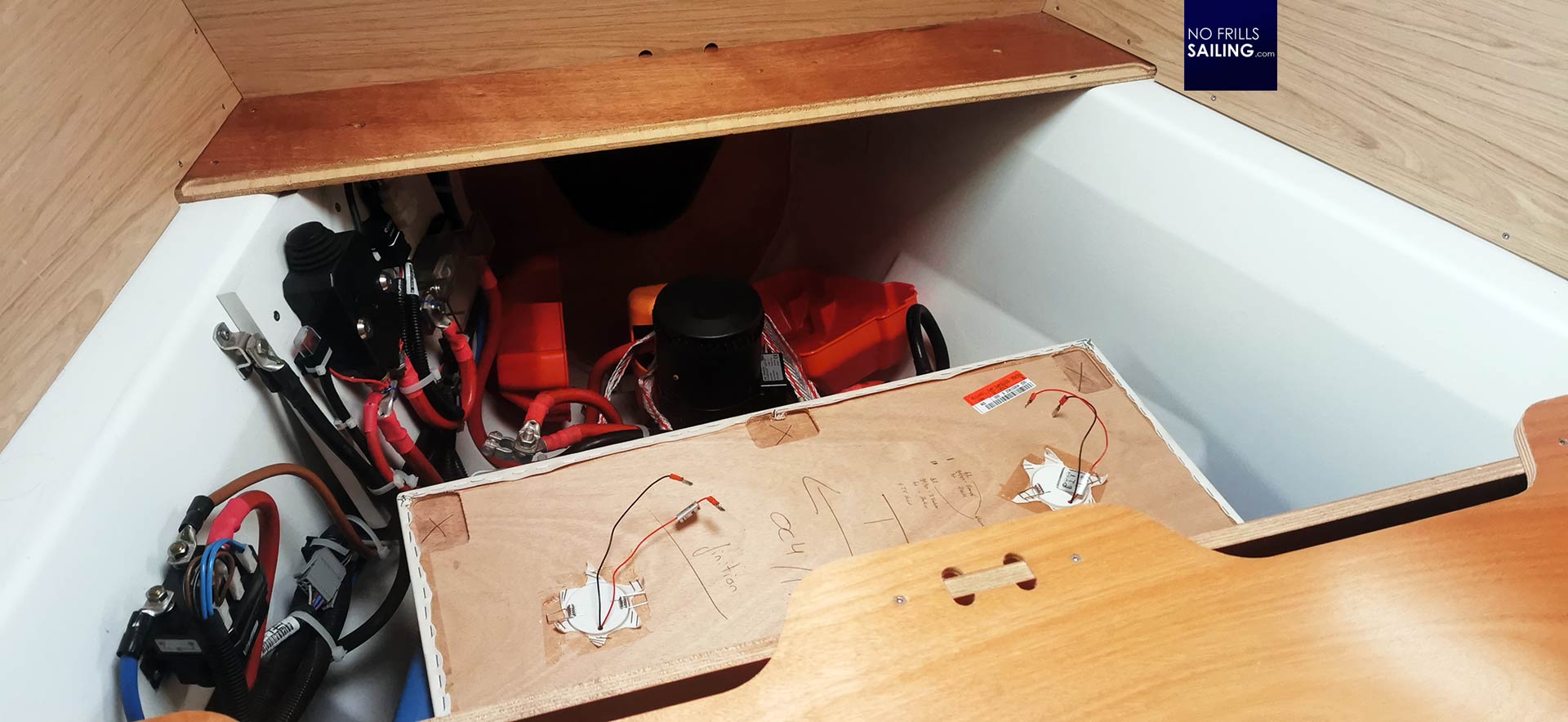

“Most modern yachts built after the year 2000 do come with gel-batteries which are basically maintenance free”, says my colleague, checking with his LED-light every connector, every battery and every cable for unusual signs. Older boats or boats of a cheaper price range come with classic lead-acid-batteries: “Have them replaced immediately”, my mate recommends: “The new gel-types are definitely connect-and-play and much safer.” On our Oceanis the impression from the engine finds its sequel here in the battery compartment: It looks and even smells like the boat had just been leaving the yard in France. All is fine.

Going to the owner´s cabin in the front, we as well take away the berth´s covering panels to check the internals of the bow thruster. “If you detect smoke residue, black areas and even signs of small fires that´s an unmistakable sign for misuse of the bow thruster.”, he explains. Sometimes these crucial parts of the boat can start to smolder when used too long and even catch fire. If you see this, be extremely cautious – or better let go of the boat. “All is well here”, my mate says and we check the water system: He crawls in every head and cupboard of the galley to look at the fresh water pumps – a thorough test of course can only be made when the boat is in the water as now, in the midst of winter, the whole water circuit is winterized and empty.

Back to the bilge

Down on our knees, we take off all floorboards. Most hulls of modern production boats are made of an outer hull into which an inner framework or even an innerhull acting as stringers and vertical frames is glued. He kneels down and thoroughly inspects the keel bolts: Rust is a sign of water entering the hull from outside through the keel-bolt channels. “That would be red alert”, says my colleague. Also, most yards do apply a red or yellow line – done with a water resistant marker – over bolt and nut. “If this line isn´t congruent anymore that means that either the nut or – far worse – the bolt has moved. This of course is indicating something´s wrong with the keel-hull-connection.”

He also looks for cracks, especially around the keel bolts and thick washers which would indicate violent grounding-events or a loosening keel. Again, our Oceanis boasts with a clean white bilge free of any cracks. The apparent lack of dirt again is highly pleasing because it is a sign that this owner really cared for his boat and kept it always in good shape: Definitely increasing the value of this yacht, making it more attractive to potential buyers and – best of all – it spares my company re-investing money for a refreshment before selling it again.

Furniture, wooden carpentry and comforts

“Now, we have checked the big things and I must say I am rather pleased so far”, says my colleague. We could leave now, because all that is left to do is the “cosmetics”, but now that we are here, let´s use the time wisely. All cushions and most decorative elements are taken off boat and stored in a dry place at the owner´s home – so that´s a good chance to check the woodworks and furniture of the boat. “In most cases that´s where we see the most wear and tear”, says my colleague: “And here is where the potential buyers will try to use the ditches to talk down the price.” So, knowing where the scratches are may save a negotiation.

We of course detect some minor scratches, some dents and tics in the veneer-covered plywood furniture – something we had expected to see because that´s what happens over time on a boat. In rough seas a steel knife would fall off the table hacking a dent into a floorboard, one night going down the entryway a life jacket´s steel harness ring, taken off all too early, may create a scratch in the wooden bulkhead. “That´s normal. But nothing too serious because it´s not affecting the structure of the boat or the safety”, says my mate: “But on the other hand, future buyers will invest most of their time when looking at the boats counting the scratches trying to get the price down.”

Value in- and decreasing factors

Which brings us to the factors influencing the value of the boat. Entering the Oceanis´ cockpit we notice some enhancements the owner has made over the years to the boat: For example, the Genoa winches had been upgraded to electric. That is a good thing – on a boat of this size having electric winches for the main halyard (which is in this boat originally) and even for the Jib/Genoa sheets is a definitive plus. “Nobody wants to grind the big sails anymore on a cruiser”, says my colleague and checks for the quality of the installation, both inside and outside of the boat.

The owner promises to provide us with all invoices of further enhancements of the boat. One of the biggest points are the sails: Last summer he took off the standard Dacron sails and replaced them by Elvström Epex laminate sails. That´s definitely a huge pro for the boat´s sailing capabilities but a double-edged sword as well: Many “sailors”, especially buyers of secondhand boats, do have to care much more about their available budgets. They mostly simply don´t attribute too much value to good sails as they have to calculate very tightly and want to save as much as they can. Having these brand new sails of the highest quality may add significantly to the boat being an attractive sailing yacht – but they make it also more expensive to comparable offers with poorer sailcloth. And thet may limit the circle of potential buyers for us – increasing the risk of this trade in.

Something that is similarly either good or bad for the boat is the decking. Back in the day this Oceanis was just fitted with Teak decking in the cockpit. The owner upgraded his boat with a custom-made Cork decking for the sidewalks and the fore deck. It´s a great quality, some 7 millimetres thick, well made, perfectly glued to the boat and the craftsmanship is flawless. But as my colleague states: “It is something many people won´t find attractive. It´s simply in the eye of the beholder: Either you like it or not. I know many sailors who would prefer bare gelcoat over this Cork. And besides, even when bot Teak in the cockpit and the Cork will have been naturally whitened to their normal grey-color, you will always be able to tell the difference between cockpit-decking and the rest.” This may be a value limiting factor – and most certainly limit the circle of potential buyers as well.

Anyway, these are merely „luxurious” worries as we are talking about cosmetic effects and discussions about “is it worth it?” rather than “can you bear it?” As my mate puts it, better sell a used boat that is too good equipped than one that has a list of shortcomings. What definitely has to be taken off the boat are the numerous decorative thingies here and there, like “maritime” style coat hooks, framed pictures or other personal elements the owners had applied to the boat over time: “That is relatively easy, the only downside is that they all leave holes which can be closed – but it will never be looking like new.” On the other hand: That is why this is called a “secondhand” boat.

Assessing the value of a used boat

We conclude our visit to the Northern German coast – not far, by the way, from where I had bought my first boat, the OLIVIA, just 2.000 metres upriver – with a small chat with the owner. Our impression of this Oceanis is absolutely good. The boat is in tremendous shape seeing far less signs of wear and tear than one might expect for a yacht three years in use. The structural and technical parts are in perfect shape – the second appointment fully rigged and in the water will add to this impression for sure. The only downgrades we could detect have all been just cosmetic nature and we both have a very good feeling about this. In a market that is virtually empty after the Corona-boom of 2020, this Oceanis will definitely be a very attractive offer on the secondhand boat market.

Driving home (and switching the AC to max heat, burning my arse on with the seat-heating) we discuss what is up next with this boat: My colleague will now go through the specs of this boat, crawl all invoices of the later installed equipment and compare the boat´s value with current Oceanis 41.1 offers on the internet. Together with a standard tool for evaluation of the loss of value of boats over time, he will produce an official document which will be the base of our trade-in offer to the client – and later of the asking price of that boat on the market. What an exciting day with so many impressions and learnings. To be continued …

You may want to read these used-boat related articles too:

Books I recommend for secondhand boat-buyers (books are in German though)

A trip to France: Three secondhand boats I took a thorough look at

Refitting a bargain hull?