Oh man. Quite some busy weeks this year – having been to Les Sables only one week ago, I returned a few days ago once again to finally inspect and take over another catamaran from the shipyard. Being a lucky man that I am, it was again a wonderful sunny and mild week with temperatures nearing 10 degrees Celsius, a brightly shining sun and thus my mood was on an absolute high, having just escaped the freezing grip of the onset of winter back in Germany. Even more lucky I felt when I called Andrea Lodolo, asking if he would be available for another flying visit – and he was!

Walking down the pontoon I admired the classy lines of his Rustler 36. This boat is a 10.77 meter long classic, built by Rustler yachts of Falmouth, England. It has first been built in 1980 and since then more than 120 units had been built. She is well known for her exceptionally rugged structure, practically unbreakable and is therefore one of the big names when it comes to “go anywhere”-boats. 36 feet is a size that is very well manageable by a solo skipper and sustainable for two people. Rustler still offers this boat the same way it has been built since almost 45 years. She is beautiful, indeed, appealing to the classic eye, a long keeler I´d love to sail.

An invitation I couldn´t decline

Andrea Lodolo, skipper of BIBI, as the yacht is named, kindly invites me to come aboard and as if the warm sunshine of this glorious day isn´t enough, offers to have a little fun dash out: “Wanna see how she sails?”, he asks. And so he starts to ready the boat. As my punch list for today´s work is completed, I happily grab my oils from the car (I am always ready to cast off, equipment-wise) and join Andrea in getting ready.

Andrea Lodolo is a 52 years old skipper from Italy, a highly respected business-man and focused professional mariner. Having transferred his activities largely to entrepreneurial activities, he shifted his attention and basically his whole life to sailing. Officially entering the attendance list for the Golden Globe Race 2026, BIBI is his boat of choice for this notorious circumnavigation – surely a good choice, as this is the most popular boat within the Golden Globe Race-fleet. With a sturdy 7.6 tons full displacement hull (long keel!) this boat has 3.5 tons of ballast, which is a nearly 50 per cent ballast ratio – something that is very re-assuring for entering the Southern Ocean …

Casting off a couple of minutes later, I remain on the jetty and ask Andrea to steam past my camera lense a few times, just to admire the full lines of the yacht. She appears to be larger than 36 feet to my eyes. A relatively high freeboard, a nice sheer line and a good visual balance between hull and cabin roof: A beautiful, timeless boat for sure. Andrea collects me at the pontoon, we start to head out from Les Sables Port Olona into the Biscay.

Feeling at the helm

Taking away the fenders and dock lines, Andrea hands me the tiller to steer out BIBI. It´s my first time on the helm of a full displacement boat. Often I had read about the alleged sturdiness or portliness of long-keeled boats and so I was keen on how she felt: Is it really such a difference to the modern double-ruddered light-displacement yachts of current days? I´d say yes, indeed! First of all, it is always a joy to have a boat with a tiller. I like steering wheels, of course, as they are convenient, look very sleek and “yacht-like”. But honestly, nothing beats a tiller in terms of directness, rudder feedback and reaction time.

The latter in brackets: My first impression of the Rustler 36 under engine at the helm is very different from my past experience with modern boats. Whereas a boat like my First 27 SE was extremely light-footed and nimble on the helm, almost instantaneously translated even the smallest impulses from the tiller into course changes, the Rustler seems to take an eternity until she is moving. But then it is also quite hard to stop the impulse and adjust course. It takes a few minutes to getting used to this but I soon understand that this full displacement hull is kind of inert and needs a lot of tactfulness. On our way back into the marina I will again get the opportunity to be at the helm: By then I could get a better feel and my movements became less awkward and clumsy.

Hoisting the canvas, solo-sailing mode

Andrea in the meantime is back in the cockpit and we steam outside between the breakwaters. He points his head towards the long walkway that leads up to the starboard side lighthouse of Les Sables and says to me: “This is where the masses will round up when the Vendeé Globe starts.” And he means: When the Golden Globe Race will start. We steam past the lighthouses – a large Atlantic Ocean welcomes us with a huge swell. Let´s roll!

It is absolutely interesting for me to watch Andrea Lodolo: As a skilled sailor and solo skipper who is currently training in Les Sables on a daily basis, often dashing out twice a day, there should be a lot of things to watch, to notice, to learn from. And right away it started with something I had not expected: Andrea turns the boat into the mightly swell and adjusted the windvane of the self steering mechanism. I was eager to learn how the wind pilot works in real life after writing my article last time and here we are: A live demonstration!

After adjusting the pilot, the boat steers itself dead into the wind. I watch the windvane work and it is absolutely exhilarating: How nimble and easy the vane works on the small rudder behind the boat. It keeps BIBI right in course and not even the highest waves rolling in can put the Rustler off course. Which leads me to the next Aha-moment.

Quite some tough free waves …

Whilst Andrea is standing at the mast foot working to get up the first 2 or 3 meters of the mainsail, later returning to the cockpit to crank the halyard winch. The waves are pretty impressive: Les Sables d´Olonne has a tricky entrance to the harbor with a zone of, I´d say, half a mile where the Ocean floor seems to produce high and steep waves. It gets better the more distance one can get from the harbour, but immediately after/before the entrance, it´s the worst.

I don´t know if Andrea did this for training purposes, but he decided not to steam into the calmer waters but to hoist sails just right here where the Ocean was literally boiling. The waves had an average height of at least three meters, which already is pretty intense. But every fifth or sixth wave was a true freaky one: A wall of fierce foaming greenish water with white foam caps was travelling towards the boat, forcing her bow pointing up towards the sunny blue sky, skyrocketing the ship up.

“You do not ever do this in a modern boat!”, I always thought to myself, being on the crest of the wave, as BIBI put her bow down and shot sliding down the wave, gaining momentum. The first few times I really feared the hard slamming, the wobbling of the mast, the grim sounds a suffering rigging will make. But apparently … nothing! Nothing at all! I mean, no slamming, no splashing into the water – not even some rocking. Just a smooth and gentle movement, calm and re-assuring. It was like a revelation for me! Literally, in those conditions, steaming 90 degrees dead ahead right into the oncoming steep waves … you never do this is a modern boat.

Finding the balance

I calmed down inside. Letting go my initial presentiment and, leaning back and enjoying the ride. In the meantime, Andrea had hoisted the main and veered away, quickly unrolling the Genoa. I killed the engine upon his advice and got u in the cockpit again to watch the second lesson of the day: Finetuning the boat´s course. Unlocking the helm and taking a sharp turn to portside, he started by roughly aligning the boat to a beam reach. Then he fixed the tiller again to amidship and started to work the windvane.

„I´ve added some marks on the trim wheel”, he told me: Pointing to white markings, Andrea found quick links for the main points of sail. By using his “remote control” (you may read the details of this mechanism by checking the article here) he can now quickly bridge the gabs when changing to a new point of sail by just turning the trim wheel and have the finetune later. This system works pretty fine and again, I was puzzled by the effectiveness of the windvane. As I am only used to engaging and disengaging electric or hydraulic auto pilots, this simple yet ingenious mechanical system fascinates me quite much!

The boat is held on course in an absolute balance. The instant reaction of the windvane causes to the boat to steer a slightly zig-zag-course, which in the midst of this violently boiling seas went totally unnoticed. Andrea tells me that the windvane has three settings, for “light”, “moderate” and “heavy” winds, which makes it even more adjustable. I really begin to be a big fan of such a steering mechanism!

It is only then when Andrea starts to trim his sails. Up until now, he was just caring about getting up the canvas, find a general course, finetune the windvane to the exact course. Just now he leans back in his cockpit and literally for the first time of our dash out, he seems to look up and into the very sails. Checking Windex and the tell tales in sails, he finally starts to trim the sails, easing a sheet here, cranking in another sheet there. After some 15 or 20 minutes he finally looks at me: “Now we have it!” Smiling. There it is: The equilibrium.

Deeply impressive: Rustler´s sailing performance

This is the first moment Andrea´s strain eases. He smiles for the first time. Looking out and around into the waves. “This is why we do this, right?”, pointing to the incoming waves: “Look at this grandeur! Isn´t it amazing?” While we chat, he offers me a sandwich he brought on board, a tasty, fresh French baguette with jambon et fromage, the salty delight is a treat for my stomach, still a bit stirred up by the rollercoaster of Les Sables´ harbor entrance.

The Rustler marches forward. Adjusting the windvane Andrea gets to sail the boat in all major points of sail, just to show me how it feels like. I am amazed by the seaworthiness and, much more, by the seakindness of this boat. What felt like a slowly turning supertanker just 60 minutes before, is now a lively, nimble and impressively quick sailing yacht. The best part of it is how she copes with the swell, which is really a gamechanger for me! This classic long keel full displacement hull is by far the most comfortable boat I ever got sail in my whole life! I´ve never experienced a boat so smooth, so gentle, so calm and quiet like this one. “Now, perfectly in balance, well-trimmed”, Andrea says, “she could be going on forever …” I nod, knowing that in his mind he visualizes himself already tackling all the offshore-adventures I is about to set out to. And now I indeed understand why this boat is the number one choice for most of the previous Golden Globe Race attendants: Three and four meter waves like we are experiencing right now seem impressive, and they surely are. But they are nothing compared to the violence and rage the Ocean can throw at a boat in the Southern Ocean. In this, having such a kind boat, stable, stiff and remarkably strong, is not a bonus, it´s simply a must-have.

A rugged cruising classic

And she is pretty quick indeed! In fact, quicker than I had thought: After Andrea had found the right trim for the sails and once she set of to spring on a beam reach, she easily reached 6 to 7 knots. I am sure there is potential for more speed – no planning of course – but a speed that will make even a circumnavigation go by relatively fast. Jean Luc Van Den Heede won his Golden Globe Race 2018 on a Rustler 36 after 211 days at see.

Of course, this is no comparison to a modern planning or even foiling high performance yacht, like CHARAL or MALIZIA, which do the same route in 75 days, being three times faster than the Rustlers. But even an average speed of 5 knots for the Rustler, taking on the 24.000 miles adventure around the world is a good speed, I´d say. Or let´s put it this way: I had thought these boats were slower.

Andrea is in his element. He seemingly relaxes by the minute. Now, that the work is done and the boat had found its equilibrium, perfectly trimmed, the windvane doing its job, he can let go: Maybe he is in his equilibrium now too? It is often said that sailors and boats are a unity, forming a bond, being able to read each other and react. Maybe that´s the state he is now in?

Modern hull design vs. full displacement

Every nice thing has to find its end, finally. After three hours out in the swirling green of the Biscay he tacks BIBI and puts her to an upwind course, the last point of sail to check on our little sea trial. Amazingly enough, the boat sails extremely stable and there is no difference in speed: We are clocking a steady 6 knots. Andrea furls the Genoa as I start the Diesel, takes down the mainsail and after passing the lighthouses, being inside the Les Sables channel, the boat stops to move around. I take the helm, thinking about what I had ultimatel learned today.

First of all I am amazed by the stiffness and seakindness of the boat. This is really a completely different game compared to the flat, thin modern hulls. They may be far superior in light and medium conditions, but I am sure if we had done the stunt in the high waves with a modern boat, we would have seriously endangered both the rigging and maybe the structural integrity of the boat. I´d never have done this with one of our boats, for sure!

Secondly, and that comes with the seakindness, the Rustler was absolutely “quiet”. I had never been sailing on a yacht so quiet, without any noise! Of course, the free boom did some clanking around during hoisting of the mainsail, but apart from that, it was absolutely quiet. Just the noise of the waves and the hollering of the wind around us, an occasional horn of a fishing boat nearby dancing fantastically on the wave crests as we did. So quiet. Both things lead to a deep trust in the safety as a passenger on board. It´s like a built-in life insurance. I trust this boat!

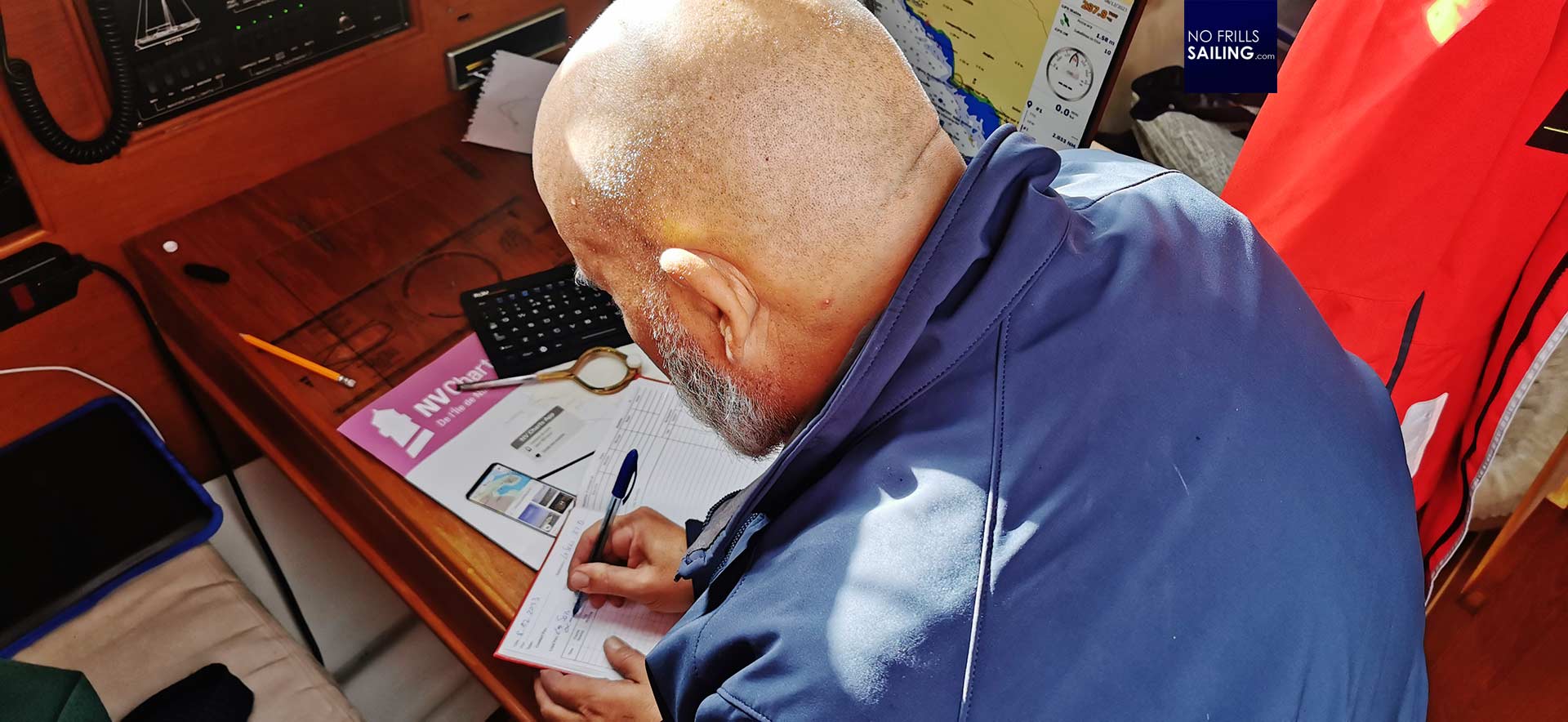

I say Goodbye to Andrea and thank him for this impressive demonstration of what BIBI is capable. Being a pro-sailor, he just briefly notifies me as he is busy completing his logbook with a proper entry for this day. A good sign, a proper seafarer, a serious GGR contender. Driving home back to Germany I think much about my learnings, and I must smile suddenly: My new boat is also a classic. Although bearing a more modern hull design and a moderate fin keel, the Omega 42 is not a flat planning boat, but an elegant and fast displacement yacht. If she offers just half of the seakindness of the Rustler 36, I will for sure be a happy man.

You might as well be interested in these related articles:

Hull design and different keel types

How modern hull design affects internal volume

Talking to Rob & Tom Humphreys about modern yacht design