Now it got me too. Inevitable as it was, it seemed so far-fetched that I´d never have thought it would hit me. But now I admit that the Biscay Trap, that so many countless other sailors got before me, has now tied me up and doomed me and my crew to do nothing but wait. Tonight, on the mark at 0300, we untied our catamaran and started to cast off – and failed. It was a combination of strong winds blowing us back towards the pontoon and too little space for manoeuvering as we´ve only had 2 metres the most in front and behind us. No chance of squeezing the cat out of this. Or let´s say, I refrained of trying weird ideas as this was not my own boat and apparently the was no pressure to do so.

But the disappointment weighed in harshly as I sent back the crew to their quarters, but remained on station and alert to check weather. That gave me the rest. Or let´s say, it is a mixture of disappointment and luck. Weather situation out on the English Channel over night somehow worsened and apart from a 2-3 metre wave-system and battering 25-28 knots, there was a storm warning upcoming with gusts of +50 knots and heaven knows which perilous situations our precious catamaran would have had to endure. But let´s start at the beginning …

How it all started in Les Sables d´Olonne

You might have read my last article on the RESIDENZ, the second of the Excess 11-catamarans I was commissioned to deliver to their owners. This cat however was northbound to Germany, a 1.000 miles sailing trip I was so much looking forward to as it resembled identically the last year´s Bay of Biscay and Channel-crossing in FREE WILLY. The memories of this sailing venture are still strong: What a happy cruise this was, sunny weather, nice winds and lush sailing. Well, I thought – better: hoped – for a similar experience.

As we casted off in Les Sables on the 3rd of August at least our spirits were high. “We”, this is Andi, a sailing mate who was aboard FREE WILLY too and whom I detached from the crew upon taking over in Porto. And there was Martin, a dear friend with whom I can look back to this wonderful sailing adventure in the Oceanis 30.1 prototype to Sweden. A good crew, capable and competent, willing to set sails. We had stowed the catamaran with enough food and water to make the whole trip in one leg: As Corona is still a thing, UK is forbidden, the Netherlands are high-risk area and so I advised to make the whole trip in one big leg. Not so much of a vacation – more of a thorough trip to foster offshore experience.

At first there was no wind at all, instead a misty, wet fog and a long old swell from a distant storm. The cat went up and down, gently, but relentless. Later wind set in, I could hoist our sails and off she went. The catamaran sails nimble and fast – for a boat class that has a reputation of being slow and sluggish. In fact, wind increased that much that I had to put in the first reef into the main quickly. Seastate further deteriorated and the long old swell was quickly overtuned by a shorter, ever growing wind sea building up waves of 1.50 to 2 metres.

Seasickness: A first dropout

Which was a good thing at first. We flew pass the Ile de Yeu much, much quicker than I had thought and after I returned from a quick nap I saw that we neared the Belle Ile also much quicker than estimated. I was in a good mood until – well, until sea sickness, the curse of all sailors, struck again. Andi sat there in the cockpit, a face as white as a marble statue, pearls of sweat on his fore head. He tried to calm us down and hide his condition, but we all knew that it was over. Shortly after I relieved him from his watch, taking over and sending him down to his berth, he came up again, running to the stern and puked his guts out.

Poor guy, we thought, wished him well and gave him this multitude of good advice, like “drink much”, “don´t eat fatty stuff” or “lay down and sleep it away”. I the end, it did not help. Andi was taken out of service and faced a brutal sea sickness and nausea for the rest of the trip. This was the first brick taken out of the wall, later making us realize that we were really trapped.

Now, with one out, our watch system was at risk and although Andi – as heroic as he was – insisted of standing his watches, we knew that his level of readiness was far from 100 per cent. Too less to have the boat operated in a safe manner, for sure. All we could do was to hope for a miraculously quick recovery and that the weather – speak: the sea state – would calm down a bit to make for better conditions. Well, all hope was of no avail.

Upwind beating in a Catamaran

Although the catamaran sailed like hell, it did not change for the rocking motions inside. Andi resided in the forward cabin which naturally was most prone to heavy rocking. We offered him the emergency berth in the saloon where we found him trying to sleep and keep away the somber thoughts of nausea and puking. Sometimes he would get up, dress and accompany us. Trying to smile he stood his watches which we appreciated, as after the first 24 hours first signs of wear and tear set in.

Wind shifted and we altered course: Upwind beating in a catamaran is not something these boats are originally built for. Nevertheless, judging from what I have heard about multihulls before, this particular boat sailed exceptionally good. For a cat. Upwind an AWA of 50 degrees was possible but only in light winds and no waves. Now with lots of waves which made our cat´s bows plough deep into the waves, almost stopping the boat, we had to veer off to some 60 degrees. Anyways, right now the course was more than perfect for passing Belle Ile and so we dashed up northwards.

Andi kept on his good spirit and the awkward mixture of feeding the fish and trying to fulfil his crewmemeber´s duties. The logbook´s entries keep on telling a tale of fast sailing. We neared Plogoff and the Pahre d´Eckmuehl s the wind eventually began to shift – and not for the good.

Sacked …

I couldn´t get it, why the hell must this happen to us? We had made such a good progress and now the wind blew exactly from the direction we had to go to. Making some 24 knots and having built up quite an impressive seas, we began to reduce further sail area and I committed my crew to at least 4 hours of beating action.

So we started. Port side was the “chocolate” bow since the catamaran favored the wave pattern coming in in a slightly less sharp angle than on starboard tack. Each tack lasted for one and a half hours, sending us either towards the impressive lighthouse “d´Eckmuehl” or away. I was depressed, seeing our hardly earned lead melting away so quickly. The boat worked hard and so did we.

A highlight was the passage of one of my favourite pro-sailing boats. Jeremy beyou´s CHARAL, a foiling IMOCA of the latest generation, flew past by us. I recognized the large, deep-black 3di-sails and the all too obvious large square topped sails silhouette. All pictures I tried to take turned out shitty so that I leastwise took a pic of our plotter showing the AIS identification of this boat. My heart jumped and I envied the ability of this racer to point up so high and speed up to 10.5 knots upwind.

Now, some days later, my memory begins to fade as so many things have been taken place since then, so I am happy to have at hand my logbook where it is written down every 3 hours: We started the tacking action at 12.30 and finally, 7.5 hours later, wind slowly began to die out. During this long day we had made good not more than 10 miles, performing 8 tacks and 2 reefing actions. We were exhausted.

Decisions of a skipper

Well, in the end, a decision was needed. I saw the crew: Tired, worn and partially sick. Because of the bad sea state and the heavy rocking of the catamaran we hadn´t been able to cook a hot meal for 12 hours or so and looking at Andi revealed that his condition did not get better anytime soon. Wind was down and quickly the waves followed, as I started the engine, pointed our bow to the Ile du Seine and announced: “New course to Brest. We all need to sleep and calm down a bit. Everything else would be gross negligence of reality.”

Although they tried to look shocked and played a bit of disappointment, I knew they were secretly happy in view of a hot shower, a non-rocking bed and a complete good night´s sleep. So I sent down the two boys and took over the watch. Already knowing what would follow from the last visit here – literally one full year ago – I asked them to get a bit of a rest as I would need them back on deck for helping negotiate the Brest Bay.

As the sun went down many fishing boats showed up. A game of jackstraws on the chart plotter, seemingly aimless manoeuvering about in search for the best fish. I switched on out steaming lights, took down the main sail and readied the running rigging, coiling up and stowing away all sheets and lines which were now no longer needed. Both guys were down below in their bunks trying to catch some sleep as I watched the sun going down.

It was a mixture of having achieved something – at least we have been sailing some 200 miles from Les Sables to Brest in again for a catamaran not so favourable conditions – and a feeling of failure as the plan, to sail the whole 1.000 miles in one big leg was now shattered. In any case, the decision to go here and land the boat for a day or two, as I thought, was the right thing to do: With Andi puking his intestines out the crew was weakened and that was really not the best premise to enter the English Channel, one of the most frequented waterways in the world.

In Brest again, still up for some hope

Brest approach is a bit tricky. The waters, for commercial big traffic, are very shallow so it is sparked with buoys, markings and lighthouses. It is a multitude of lights setting the dark night alight, navigating these waters requires an alert mind and, better so, 4 eyes. I asked Martin to join me up on the bridge and he got up quickly. We identified the lateral and cardinal buoys and – lucky us! – as it was rising tide, the boat sprung to life and dashed down into the narrow channel with 6.5 knots.

It was still 13 miles to go, 2 hours, but very interesting. Identifying buoys by their light-code is a competence any skipper should be refreshing from time to time as negotiating the nightly waters requires special abilities. I already knew what would come when entering Brest from my last time, nevertheless it´s always an exciting thing to come here: Narrow passage between Brest in the North and the Roscanvel-outlet, creating a small channel called the Goulet du Brest. Passing here is tricky: There is a shoal in the middle you´d have to pass on the left or right hand side and when arriving too late or too early, the tide can push or pull with up to 3 knots here.

Our passage was quick and without problems. Wind was down to a mere 7 knots and Andi in the meantime got up too. I advised the crew to prepare the boat, which was a kind of tricky decision: Which berth can we expect, a box, alongside? Starboard or port side? It´s always a guessing game and that is why I have always prepared all lines at all four clamps and some of the fenders on port side whilst the bulk of them would be attached to starboard side. I hoped to find a free berth for a starboard alongside landing manoeuvre. Problem was that at 0200 in the morning no marinero or harbormaster would help us …

At last, we landed! As I entered the marina we saw that every guest berth was occupied. I did had a phone conversation with Brest the day before, telling me that I should go at the last end of the visitor´s jetty where there would be a place for me but as it turned out, there wasn´t. The marina was full. So I decided to pull “Plan B”, which is always a good idea when entering an unknown marina not sure where to berth: Look out for the refueling quay as there is mostly free space to at least stay for a night. This is what I did. We tied up the boat to the fuel station and went to our bunks, the logbook remark says “Landed at 0200 – tired!”. The next morning we saw that during the night another boat followed suit with a third one finally arriving at the fuel station at noon. What´s going on here?

A new day but bad news

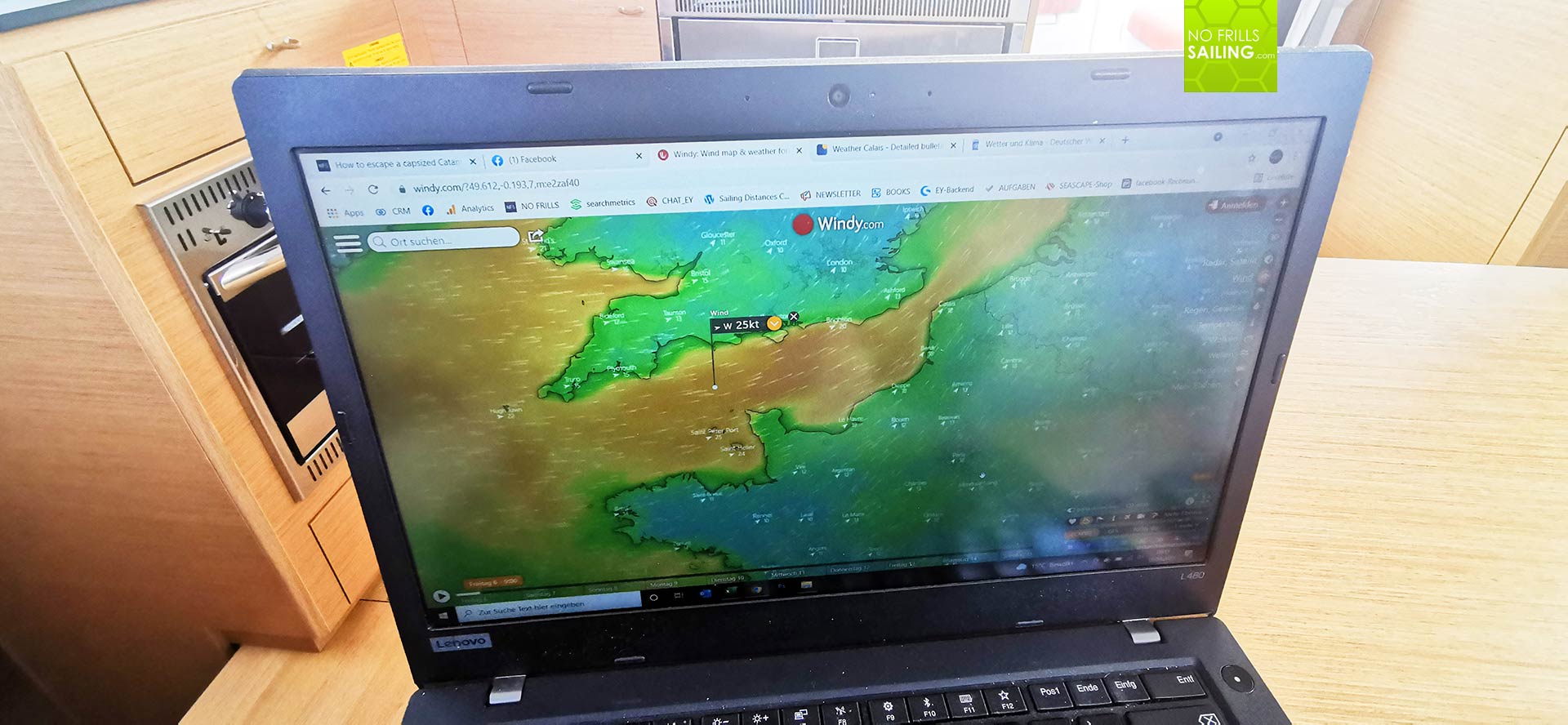

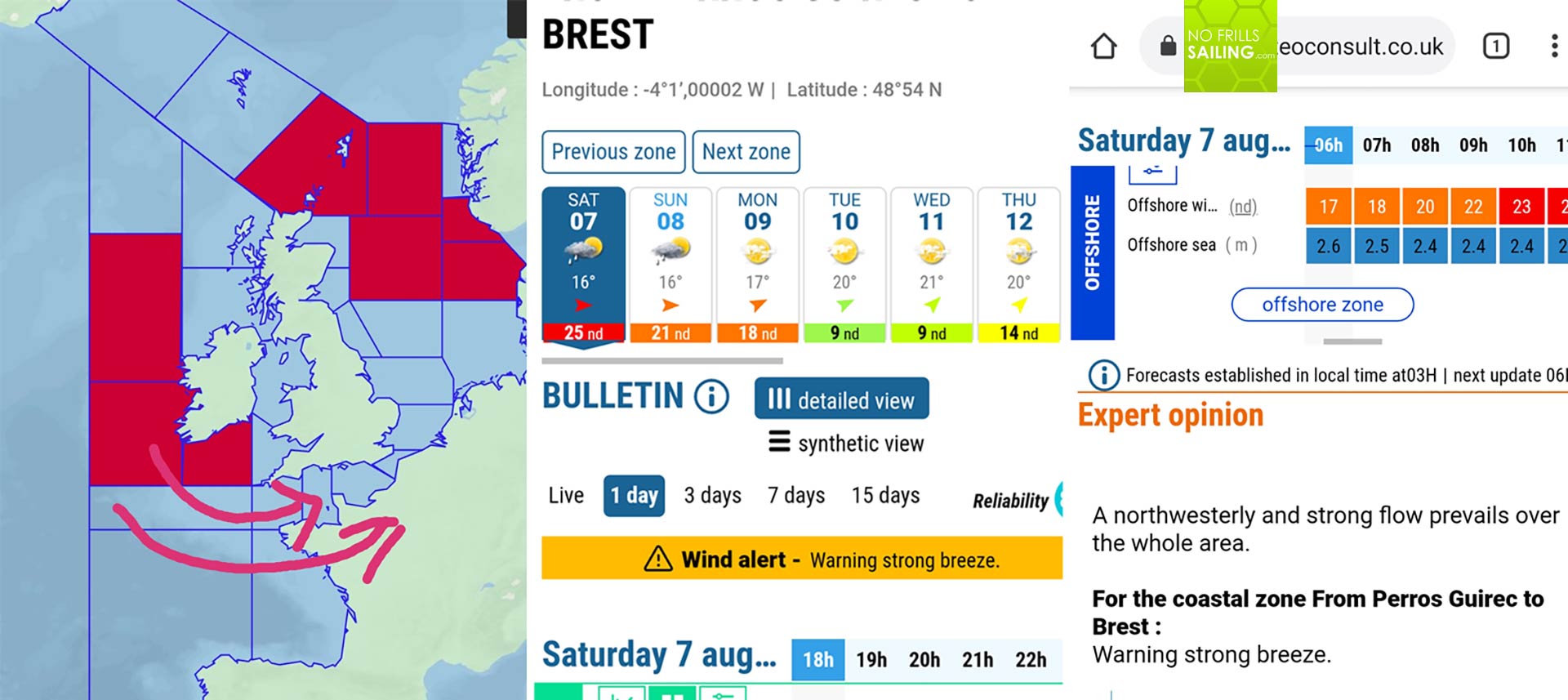

Next day we paid demurrage and I did a thorough weather research. My hopes got shattered instantly as I saw that the situation had worsened since we left Les Sables: There was a low pressure system kind of locked over Ireland that was shoveling cold air, moisture and – least favourable of them all – loads of strong wind into the Western Approaches and thus into the channel. We expected wind speeds exceeding 25 knots and wave heights of up to 3 metres significant height. Oh boy!

Wind grew by the hour and reached speeds of up to 22 knots in the harbour. Two berths next to us I discovered the all new Boreal 47.2, a boat I absolutely adore. “If I had this boat, I would cast off any second as this is made for conditions like these”, I told my mates, but being on a catamaran, we had been confined to our fuel station berth – outside in the boiling seas was no place for a holiday machine like mine, the Boreal, au contraire, would be alive like a young fish out there.

As an instant proof of my remarks, some hours later her berth was empty. The owner had indeed been casting off into the wild stormy seas of the Biscay and possibly the channel again. Later the day the harbormaster in his patrolling rib came alongside, knocked at the boat and asked us if we would be able to re-locate the catamaran to a now available berth. The tone in his question reassured me that he himself saw this manoeuvre with doubt, I looked up to our masthead fly that was going crazy in the wind and smiled: “Sorry, but I won´t start the engines and be torn around in the harbour in these conditions.” He smiled again, nodded and agreed: There was way too much wind!

Checking alternatives – killing time

Now, what to do? We expected to stay in Brest for another two days. Two days more than initially thought. Brest is a city that has no city centre, as the saying goes. During World War 2 this town was a very important location for the German occupation forces as the dry docks were large enough for the big units. Latest in 1941 when the big submarine base, and later the huge bunker, were available to the German Navy, the city was a target for Allied bombing raids which destroyed the town almost completely. After the war, rebuilding and getting it to work was priority over beauty. That´s what you see now.

Nevertheless, Brest features some very interesting sights to see. There is a spectacular ropeway, nice hilly streets with old housing, reminding me of Portuguese town of Porto and always something to discover. Brest is most certainly far, far away from being a nice town, but the practicality in which it was rebuild and the vivid, lively feel that is bustling in the streets. We went for a long walk and it was really amazing to discover the “secret” sides of Brest.

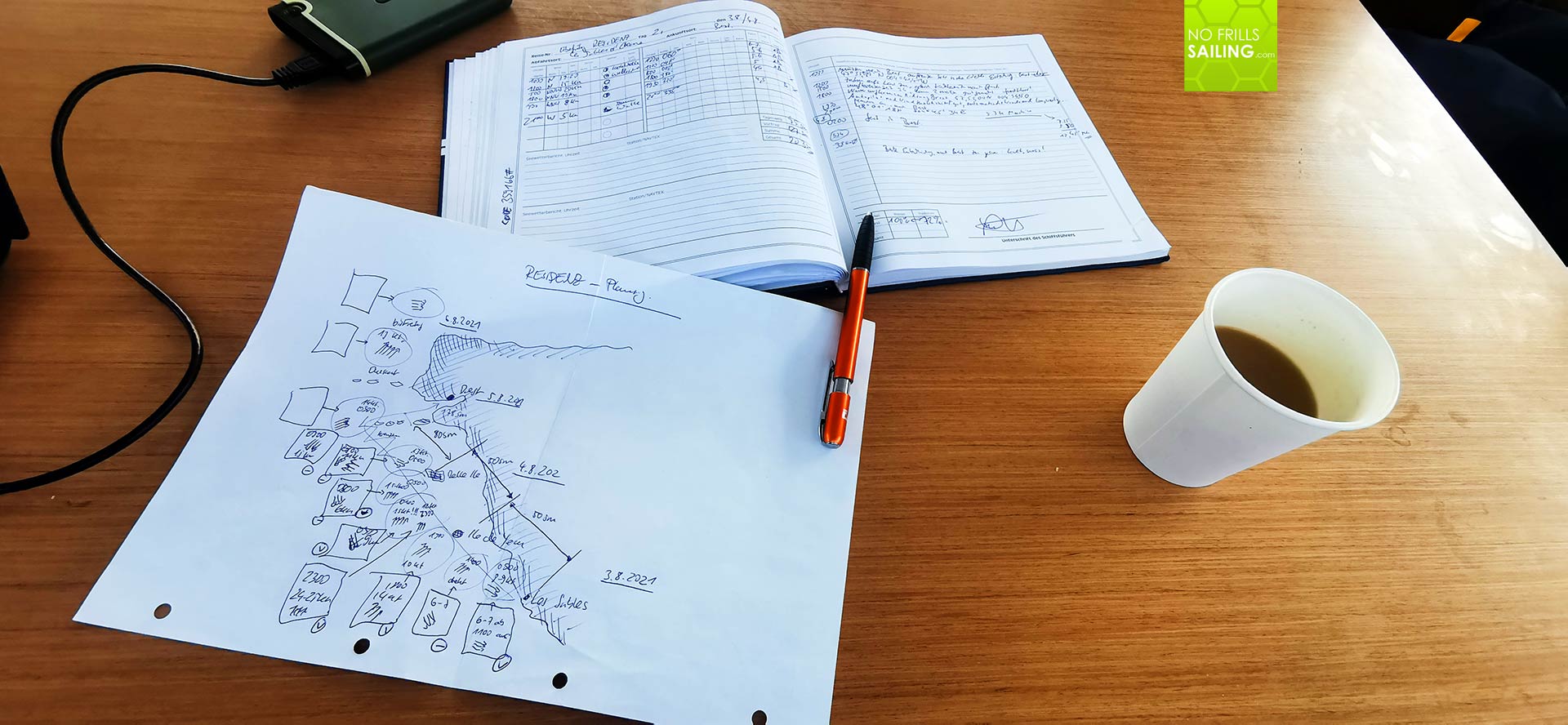

Back in the catamaran I took my time off, sat down at the nav station to start a new planning session of how we could be further going on. One thing was clear: We wouldn´t make it all the way to Germany in the given time frame, so I looked for a new destination to bring the catamaran to. That was identified as being the marina of Nieuwpoort, as Belgium was not a designated “high risk area” of Covid 19 and therefore no restrictions would apply to us. Reachable within the days we had left. Next step was to mine through my own data provided by my weather planning and logbook.

As it turned out, our catamaran would be making an average speed of merely 4 knots when forced to upwind beating and prone to high waves. That was the new speed I took for granted for my latter calculations. I then checked the all-known sources for wind prediction and it did not look well. The low pressure system was still locked over Ireland, shoveling more and more wind into the funnel, that was the English Channel. Nope, that did not look very well indeed.

Bad omen or good harbinger?

I told my crew about the situation. Naturally, when you are not responsible for the boat you are on nor responsible in any case, you see things a bit less worrisome. Not being the skipper means that you do not have any ties to the boat you are on and have no repercussions to think about your actions and decision might have. That is a natural thing and normal. Thus, my mates smiled and told me they didn´t care about waves or wind speeds, they wanted to sail on. I had a hard time explaining my somewhat reluctant standpoint. Right in that minute, heavens sent me help …

A big powerful rib of the French Marine Nationale was coming in, accompanied by two more ribs. A tow rope went from his stern to the bow of a 45 feet sailing vessel. With its blue flashing lights activated, the police-rib towed the apparently crippled sailboat into the harbor. Engine was running and crew all on deck, but nobody on the helm. Apparently, the boat had a broken rudder shaft or mechanics connected to the rudder rendering it disabled. The ribs had a hard time pushing the boat to the pier side that had been cleared of boats minutes before. I looked to the crew and nodded: “This is what happens outside”, I said. Knowing that the reason for this could have been anything else too, but it made a point.

Later the day, we went for a beer in the city, I saw a French submarine, possibly Scorpene class. Which is always a nice sight: I love submarines and as a young boy devoured every movie and book available. Now, with Martin as part of my crew, it was even cooler: Martin, an actor, played the part of Fähnrich Ullmann in the best submarine (and one of the best anti-war-) movies of all times, “Das Boot”. Everytime I sail with him, somehow, a submarine emerges. And here we were, standing and cheering as the submersible slowly slipped into harbour. This, I thought, might also be a good sign, maybe things were about to brighten up? (Actually, the real U-96 had been stationed here, in Brest, not in La Rochelle, as the movie suggests …)

Trial and fail

Well, it did not. Somehow, I can´t recollect why, I figured that it might be a good idea to cast off the next morning. With high tide at 0320 I told the boys to get up at 0230 to be on our way at 0300. There was a drop in wind speed predicted for the next 3 hours, which I thought we could use to steam the 13 miles upwind, turn sharply to the right, rounding Ile Ouessant and have the sails up on a broad reach. Then we would be dashing northwards on 030 degrees clearing the Channel and reaching UK-waters the next day. I somehow blocked the wave height out of my “plan”.

We went to the bunks early and got up just in time. With our eyes still clotted by sleep, we prepared ourself for casting off. I started the engines and we took away all land lines in spite of the fore and aft one. Lucky us! As there was another boat just in front of us and a big power boat right at my stern, I knew, I would not be able to veer away from the pier the classy way: Manoeuvering a catamaran is not done by means of bow thrusters (there are none) or rudders (they are fixed in midship position). This is usually done by counter-rotating the screws. So, normally you would be fendering the bow and rotate the catamaran still tied up with a spring-line and the push it away with full astern. Not possible this time.

I tried three times to get away from the jetty but no matter how hard I pulled the levers, the bows did not move from the pier. As wind was coming it land-wards, our high freeboard was acting like a sail, pushing us firmly to the jetty. “No way, boys”, I resigned – this manoeuvre was not working. As the catamaran was not my own boat, wind speeds much higher that the predicted 7 knots (they were more like 17 knots actually) I quitted and told them to go to bed again. Knowing that wind should be shifting to West the coming 3 hours, I postponed casting off to 0700 a.m., hoping that there was still enough time to utilize the tidal stream.

Thank god we kept tied up!

There was not. I couldn´t find sleep after the cancelled manoeuvre and stayed up all the coming hours. I began to consult more weather forecasting websites, as the Deutsche Wetterdienst, German Weather Service, which provides very accurate raw data for the Western sea areas, the UK weather service and many more. More and more I came to the conclusion that it was indeed a good thing we couldn´t leave: The steady low pressure system over night had triggered sea state warnings for the whole English Channel with “small craft advisory”. For some areas a gale force 8-warning was in place and all graphic presentations of the current and coming status in the English Channel went from “orange” to “red”. Well, thank God we did not get out of that berth!

I double- and triple-checked my data and came to the conclusion that finally the “Biscay Trap” had us. Having read so many times in books and on blogs of sailors that they had spend days, sometimes weeks, bound to the harbours because of bad weather, had finally now as well hit us. Nothing special so much, as many facebook-friends confirmed my status, but nevertheless a bit disappointing. After my crew got up later I presented the new findings: Giving in to the God of the Winds is never satisfying, but facing these conditions, the decision was absolutely right.

I prolonged the demurrage for the catamaran for another three days as weather forecast predicted that the worst would be over by then. Later that morning a short window of opportunity appeared with wind dropping to 8 knots. We untied the catamaran and re-located to a now freed berth vis-à-vis, making the harbormaster happy with his fuel station ready for work now. Wind soon re-appeared and speeds exceeding 28 knots – in the harbour!

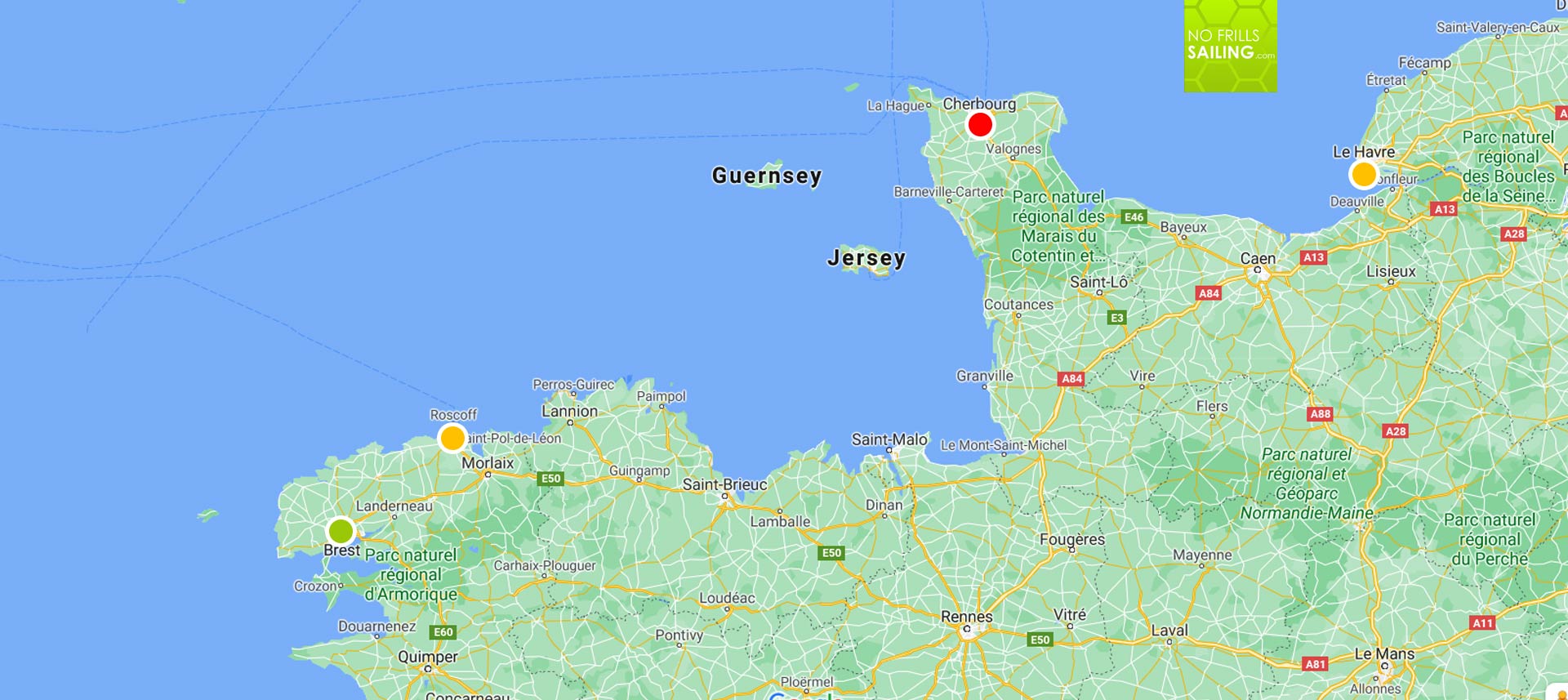

I again planned the next steps: Next available harbours would be Roscoff, Cherbourg and Le Havre. Cherbourg refused a berth upon request as upcoming Fastnet Race was due to have the finish here: Some 400 boats must be housed there. So, sitting on the cat, wind and rain battering the saloon, I hoped for a positive answer from Roscoff, maybe Le Havre: “Leaving that damn Brest tube is now priority!”, I said to the crew. With Belgium also now out of reach in our time frame, my aim was to at least escape the Biscay trap and have the boat tied up in the Channel. Well, we will see …

You might also be interested in reading these articles:

All articles related to the Excess catamaran

Heavy winds to Brindisi

My first foul weather experience